| Getting acquainted with Unusual Voices | ||

|

FanFaire

Interviews |

||

|

FanFaire

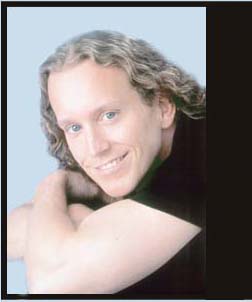

interviews DAVID WALKER, countertenor Interest in Handel's operas and early music in general has been rekindled in the last several years, and with it a demand for the countertenor voice. Indeed, Handel's operas appear to be coming back into the standard repertory, and opera companies that have never staged Handel before have begun to do so. San Diego Opera, for example, recently staged its first Handel, a highly acclaimed production of Ariodante in which you debuted the role of the villain Polinesso. In appearing with the company for the first time, you became San Diego Opera's first countertenor and the local audience couldn't have had a better introduction to the countertenor voice. The production as you know won unanimous acclaim, most especially for its excellent cast. Congratulations on a fine performance! |

Photo © Christian Steiner |

||||||

FF:

The countertenor is the voice type with which the modern audience is least

familiar. Someone seeing you sing for the first time very likely does so

with a degree of disbelief, if not confusion. Can you explain to our viewers

what the origin of the word countertenor is?

FF: Do you often find yourself having to explain to the untutored ear the apparent incongruity between the voice and the physique? DW: Certainly not every audience member has experienced a performance by a countertenor before, and I often have to explain what some people perceive to be an incongruity between my voice and my physique. But, actually, I more often will receive comments of wonder and excitement, and even some inappropriate ones!, about the combination of my voice and my physique. |

|||||||

|

FF: What is your natural voice? DW: My

natural voice is the voice with which I sing. Many countertenors take

offense to this question, and I will try to explain why. Many countertenors

feel that this is their natural voice, and they are singing with their

real instrument. They have worked very hard on reinforcing certain areas

of the voice, blending most of the registers together, etc. I never take

offense to this question, but do respond that I always sing with my natural

voice.

FF: How did you get started in music and how did a young man from Miami become interested in opera? DW: My older brother started me in music, actually. When we were in junior high school, he was playing trombone in the school orchestra, and naturally I wanted to be like him, so I started to play an instrument, the trumpet. Then as a freshman in high school I moved to the french horn section, and found my home in the orchestra! I quickly became first chair, and then drum major for the marching band. It wasn't until sophomore year of high school that I auditioned for the choir, and made it! FF: Who were/are your role models? DW: I think the one true role model I had as a young countertenor was Michael Chance. He sang brilliantly, was musically expressive, and was a great artist. I had the chance to work with him when I was performing Nerone in L'incoronazione di Poppea, and he performing Ottone, at English National Opera. I remember telling him on the first day of rehearsal that he was my hero! I think he blushed! FF: You use the sobriquet "Senesino" - we don't know much about the name except that it belonged to a famous 18th century castrato singer. Can you give our viewers a little education on Senesino and the castrato voice in general? DW: Yes, Senesino was indeed a celebrated 18th century castrato. The reason I use the sobriquet "Senesino" is because Handel wrote 18 wonderful roles for him, all of which suit my voice perfectly. So I thought it fitting to use, don't you? [Click HERE for a listing of roles composed for Senesino.] FF: One can only imagine the sound of a castrato singer - presumably no one living today has heard one, whether live or on record. From what you know, what special qualities of the castrato voice inspired composers to write music for that voice type that couldn't have been achievable with a countertenor voice? How different are the castrato and countertenor voices? DW: Actually there is a recording of a castrato available to us today. It was recorded at the end of his career, so his voice wasn't at its best (4). But it is still very interesting to hear. The castrati were basically the rock stars of their time. And when castrati were not available for performances, they would often have a countertenor sing the role. I don't really know what a castrato voice sounded like, or felt like, other than recorded history, so I can't really conjecture on the differences between a castrato and countertenor voice. FF: Is the countertenor repertoire by necessity restricted largely to oratorios and operas from the Baroque and early classical periods? DW: In a way, yes, the countertenor voice is restricted largely to oratorios and operas from the Baroque and early classical periods. FF: Aside from singing more works by early composers, how does the countertenor look to expand his repertoire? DW: I expand my repertoire by performing many recitals and orchestral performances. As with any singer, one must find what suits his voice and artistry. So in performing art song, lieder, melodie, etc., I perform only what suits me best. FF: Other than Benjamin Britten, are there other composers of more recent times who have written music for countertenor? DW: Contemporary composers are writing music for the countertenor voice. I have performed song cycles written for my voice, chamber pieces, and opera. It is very exciting to be involved with the composition of a piece, and having the composer write music specifically for my voice. Which is exactly what has happened since before Handel's time, when he wrote specific roles for his singers, like Senesino! FF: Opera singers occasionally sing "crossover" music. Is this option available to the countertenor? DW: I definitely think countertenor's could sing "crossover" music. I already do! In addition to being able to sing pop/jazz/r&b;, I do a great KD Lang! (I was even in rock bands when I was younger, singing Led Zepplin and Boston!) FF: Mezzo-sopranos often sing male or so-called "trouser roles". Are there reverse roles for countertenors in the repertory? DW: I have only performed one drag role and it was Madame de la Haltiere in Massenet's Cendrillon, and I loved it! It was a great role for me. The music fit my voice perfectly, and I wore this unbelievable body suit, enhanced with great costumes, that made me seem like a woman on stage. Then they added on a fantastic wig, and great make-up, so many audience members were rather shocked when they found out I was a man! I am not sure yet if audiences in general are ready to accept countertenors singing "skirt roles" as they are accepting of mezzos singing "trouser roles!" FF: In Ariodante, you sang a villain's role and in Los Angeles Opera's outstanding production of Handel's Giulio Cesare, notable for having brought together three of America's best countertenors, you performed the role of Cleopatra's confidant, Nireno. You have sung a number of other roles and surely must look forward to singing new roles. What particular ones do you have on your radar screen? DW:

I would love to perform the title role in Rossini's Tancredi, the

title role in Handel's Orlando, the title role in Mozart's Ascanio

in Alba, and the title role in Glass' Akhnaten. I am fortunate

to have the last item on my wish list come true, and am performing Akhnaten

in Strasbourg this coming September! (1) organum = name for the earliest types of polyphonic music, from the 9th century to c.1200 (2) fach = the German system of "compartmentalizing" voices (3) tessitura

- Italian term for "texture" describing the average vocal range of an

operatic role. If a role contains one or two isolated high notes, but

is generally written around the middle of a singer's range, the role is

said to be of medium tessitura. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Of

Unusual Voices |

| Home | Store | MusicPlanner | New Releases | Food & Music | AudioFiles | SiteMap | EmailUpdate |