|

A few weeks following the grand opening concert celebration of the

Ellie Caulkins Opera House in Denver, Colorado where he (along with

soprano Renée Fleming and bass-baritone James Morris) led the

roster of distinguished guest artists, FanFaire had the privilege

of engaging Canadian tenor Ben Heppner in a lively telephone conversation.

Casual, relaxed and often punctuated by laughter, the conversation

ranged from revisiting his younger days to peering into the foreseeable

future of the singer who by most accounts is the greatest Heldentenor

of his generation. His remarks are quite insightful, giving

a good measure of both the singer and the man.

A HELDENTENOR IN EVERYONE'S MIND EXCEPT HIS OWN

Heldentenor is of course the German term for "heroic

tenor" and trade talk for the robust tenor voice required for

very demanding operatic parts, particularly in Richard Wagner's music

dramas. But somewhat surprisingly, Ben Heppner does not think of himself

in quite that way.

"I've never thought of myself as a

dramatic tenor," he said. "That's

only part of it. I've always thought of myself as being more of a

lyric tenor, but having a voice that's large enough to do the bigger

things." Which is an apt description indeed, if one thinks

of his voice in terms of the biggest icons of the most recent decade

- a voice that can scale the high Cs with the sweetness of Luciano

Pavarotti as well as resonate with the darker, burnished virility

of Placido Domingo. [Photo © Marco

Borggreve, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

"I HATED OPERA!"

Surely one would think that a singer approaching the pinnacle of a

big international operatic career, if not already there, was born

with a passion for the art form. Yes, everyone in his very musical

family knew that he was born to sing. And yes, he sang - in choirs

and at church services.

But, "No, I hated opera!"

he confessed with a chuckle, when asked about his early feelings about

opera. "My only exposure was through

television. I tell people: where I grew up we had two television channels,

and they were called ON and OFF! I saw opera once in a while. Like

on a Sunday afternoon one may see - and I'm just making up names -

Joan Sutherland and somebody else. But it was in black and white television

in our living room and I would go, 'Yuk! Who wants to listen to that?'

And I would turn it off. So I had no idea that I would end up being

an opera singer. Even at university I wasn't really a big opera fan.

I got to like it and to love it by doing it in university and post-university

training."

That was in the mid '70s and early '80s, when he began to grasp what

opera is all about. "I didn't understand

it," he went on. "I didn't

understand being able to sing very very intimate sounding words at

a fairly high volume level. But you realize of course that those passions,

emotions - love and hate and all those things- are very very intense,

and of course you can't express hatred always loudly, you can't express

it always softly, but it's always passionate. So that was something

I had to learn - that we have to sing these very passionate things

loudly because that's what's called for. And so I started to understand

it. And then learned why I liked it, and I started to like it because

of that." [Photo credit:

Beth Bergman, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

That was in the mid '70s and early '80s, when he began to grasp what

opera is all about. "I didn't understand

it," he went on. "I didn't

understand being able to sing very very intimate sounding words at

a fairly high volume level. But you realize of course that those passions,

emotions - love and hate and all those things- are very very intense,

and of course you can't express hatred always loudly, you can't express

it always softly, but it's always passionate. So that was something

I had to learn - that we have to sing these very passionate things

loudly because that's what's called for. And so I started to understand

it. And then learned why I liked it, and I started to like it because

of that." [Photo credit:

Beth Bergman, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

"THERE'S NO MASTERPLAN."

And once he did, he threw himself into his music studies and worked

on his vocal technique, determined to make a career in opera. Hard

work and determination paid off. In 1979 he won the Canadian Broadcasting

Corporation Talent Competition. But it was in 1988 when he won the

first Birgit Nilsson Prize at the Metropolitan Opera Auditions

that his international career got launched, and thereafter took off

like a rocket. By 1992, he had sung leading roles at the world's major

opera houses, among them: La Scala, Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden,

Munich's Bavarian State Opera and the Metropolitan Opera.

When asked if this was how he envisioned his career unfolding, he

immediately replied: "Oh, I had no

clue! It just kind of happened as it happened. There's no masterplan.

I think I survived for the first three years because I was so naive

I didn't realize it shouldn't have happened this way, you know - from

nothing to all of a sudden having this big career in all these different

places. And I survived by kind of ignoring the pressure. Then by the

time I sort of realized the pressure, I had a little more experience

underneath my feet."

A dose of naivete, it seems, always helps jump-start a career. But

experience, building on extraordinary talent, has earned and continues

to earn for him virtual ownership of some of opera's most coveted

and difficult roles. Such as:

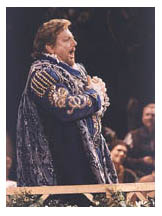

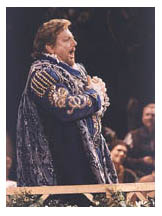

Walther von Stolzing, DIE MEISTERSINGER von Nürnberg

(shown at left in

the 1998 Met production)

Die

Meistersinger is easily the most listener-friendly of Wagner's

operas, certainly his brightest and happiest (nobody dies in the end!).

The vehicle of Heppner's La Scala debut in 1990, it became his first

calling card. Today, after having sung the role innumerable times

in concert and staged performances on both sides of the Atlantic,

he has decided to say goodbye to the role, for reasons that interestingly

have nothing to do with singing. Die

Meistersinger is easily the most listener-friendly of Wagner's

operas, certainly his brightest and happiest (nobody dies in the end!).

The vehicle of Heppner's La Scala debut in 1990, it became his first

calling card. Today, after having sung the role innumerable times

in concert and staged performances on both sides of the Atlantic,

he has decided to say goodbye to the role, for reasons that interestingly

have nothing to do with singing.

"The love interest is beginning to

be the age of my daughter. And I'm thinking, you know, it's

really one of those roles that's for a young man. I don't move like

a man of 25, I move like a man who's almost 50. So, maybe it's time.

In a sense I don't want to, but I think it's time for the role to

be put to bed." Adding,

"There are young singers and

out there and this is a very good role for them. It takes a lot of

endurance, but I think also it's a young man's role - a lot of movement,

a lot of action and passion in it. And I think it's time to move on."

[Photo credit: Beth Bergman, with permission

of Mr. Heppner]

But those of us who have become accustomed to hearing only Ben Heppner

in the role can take heart. While he no longer has plans of singing

the opera, he will ABSOLUTELY keep Walther's Prize Song in his concert

repertoire. And then of course there are his two complete opera recordings,

the 1998 Grammy-winning album with Georg Solti conducting the Chicago

Symphony Orchestra, and an earlier one with Wolfgang Sawallisch and

the Bayerisches Staatsorchester that one can always listen to.

back

to TOP

PETER

GRIMES PETER

GRIMES

Benjamin Britten's Peter Grimes is another

role Heppner's performed "a fair bit.

I did it first in

Cologne. It was a replacement for a Rienzi that didn't happen. Then

I did it in Vancouver

(shown at right, photo credit: David Cooper, with permission of Mr.

Heppner), I did it in Chicago, I've done it twice in

Covent Garden, and in Paris. And it's a favorite of mine. I think

I've been growing a lot in the characterization of that role."

LOHENGRIN

In 1989, the year

after he won the Birgit Nilsson Award, Heppner made his European debut

with the Royal Swedish Opera as Wagner's Lohengrin [photo

at left, credit: Enar Merkel Rydberg, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

leaving his first footprints as a Wagnerian tenor. He has subsequently

performed the role at the Bolshoi Theatre, San Francisco Opera, Vienna

State Opera, Bavarian State Opera, Paris Opera and in a controversial

production by the avant-garde stage director/designer Robert Wilson

at the Metropolitan Opera that never fails to invite discussion, as

it did in this instance.

"So, how did

you like working with Robert Wilson?" we asked.

"You know, the truth is, you don't work

very much with him. He doesn't come into the rehearsal except for

the last 15- 20 minutes, maybe half hour. And then you show him what

you have done that day, because the assistant does all the work.

" I like him personally, I think he's a great guy. He has a wonderful

visual sense that is spectacular. I love the look, the lighting, the

ideas that he brings. But I find it kind of amusing that he doesn't

find another way for the singers to move. He's only got the one way

- the highly stylized way. I'd like to see more variety from him and

maybe the audience should demand a little bit more.

" While we were doing Lohengrin at the Met, at the very

same time they were doing Madama Butterfly in Paris. And

I saw pictures of the Madama Butterfly in Paris, and the

costume for Pinkerton was exactly the same as the costume for Lohengrin.

And the costume for Butterfly was almost the same as Elsa's, except

Butterfly's had those panels hanging down from the arms that made

it look more oriental. And the little boy in Butterfly

wore exactly the same sort of little skirt that Gottfried wore,

and I thought 'Aren't these different operas?'

|

|

"The pictures from the Met Lohengrin of the production

and of just me as Lohengrin are fantastic! His visual sense

is so strong. [Photos

© Robert Cahen, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

"I

think what I'd like to see is - with that strong visual sense,

could he develop more of the character? You know, more of the

emotional side - that for me would be more of a powerful combination.

Some singers are very critical of having to move like that...

to stand and move in a slow way.

"I

sort of explained to him that I couldn't hold a strong isometric

tension in my body if I sang. What he was asking for was for

the muscles to be taut at all times. I can't do that. Because

within a half an hour, I will not be able to sing. The opera

is 5 hours long!

|

"I

said to him 'I can give you close to that. I can give you like you

want them, but I can't do them with tension.' Because that tension

goes up the arm and across your chest, and it would just kind of bind

you up in your musculature and you won't be able to sing for very

long. And he understood... actually he was very accepting of that.

And so, I gave him as much as I could, as often as I could and then

concentrated on singing."

This naturally led

to a more general discussion of stage direction in opera - does he

ever turn down a role because he doesn't care for the production,

for example?

"That's if I know the

production. But you know, I don't have a big, long list of people

with whom I will not work. That's not me. Which is to say, although

I don't have a big, long list, I might have a short list. All I want

is a director who is willing to feel with the music and the libretto

as being valid in and of themselves, and someone who will resist the

temptation to make some kind of political point or something. As happened

to me once in Amsterdam - they did an Idomeneo, and the director

decided to prove that this was an Idomeneo of the type of

Sadam Hussein. This was following the first Gulf War. That kind of

emphasis is going to fall down rather badly because it's not going

to fit completely. There's going to be jarring inconsistencies. So,

I wasn't very happy with that."

And as to the increased power of today's

stage director, which may have stemmed from the increasing need to

develop a wider audience for opera?

"Oh I think that's

been in place for 20 years, absolutely. It's been much much stronger.

For a long time it was the singer, and then came the time of the conductor.

You think of Toscanini, von Karajan, Wurtwängler... all of these

conductors who became very strong influences. Then it turned to the

visual side - it became the world of the director and, maybe, the

scenic designer who sometimes are one and the same. I think it's been

that way since Zeffirelli, Ponnelle. I certainly would remember in

the early '80s having said exactly the same thing. And I sometimes

I do think it's controversial just because the director gets more

column inches by being provocative rather than by any other means.

"It's not all bad, quite frankly, that the director has sort

of an upper hand. It's not all bad, because opera does need a stronger

visual sense, and that may help develop a younger audience. I'm hoping

as the boomers age, and the generation following them - that they

would start to realize the richness of operatic and classical music,

of musical textures and colors, and begin to demand more from their

listening; that they listen not just to the oldies or the new punk

bands - punk isn't new anymore - or whatever the new musical

genres may be. Of course opera has to be adaptable for their taste

as well - it has to change, and the singers too. We're essentially

artisans up there on the stage - we're workmen, we're journeymen.

We're not great artistes, we're not creative artists, we're

re-creative artists and our skill is to be able to

re-create characters in numerous different ways, at least we hope."

back

to TOP

TRISTAN UND ISOLDE

Wagner's Tristan

is one role that Ben Heppner definitely owns today, having "re-created"

Tristan in quite a few productions since he debuted the role in Seattle

in 1998.

"I've done it twice

in Seattle, and that same production I did in Chicago, and the Met

[Photo credit: Beth

Bergman, with permission of Mr. Heppner] I've

done twice. I've done one in Paris, Kupfer's production in Berlin,

I've done one in Salzburg and Florence. I'm missing something,

but I may have done 5 or maybe 6 productions."

"I've done it twice

in Seattle, and that same production I did in Chicago, and the Met

[Photo credit: Beth

Bergman, with permission of Mr. Heppner] I've

done twice. I've done one in Paris, Kupfer's production in Berlin,

I've done one in Salzburg and Florence. I'm missing something,

but I may have done 5 or maybe 6 productions."

Tristan is a role only a few tenors

in one's lifetime have the privilege and the vocal wherewithal to

sing. So, is it possibly Heppner's favorite?

"It's interesting.

It's one of those roles I never name as my favorite. But I have to

say I adore doing it, I love the challenge of the role - that's the

thing that's important to me. When I go to the theatre, there's

a sense in which I feel I have to climb Mt. Everest. You know there's

a big task ahead of you. But once you go on stage, it seems only like

minutes before you're finished. I mean, it goes by so quickly...."

How does one develop

a character like Tristan? In Heppner's case, mostly onstage in rehearsal

- except for one aria on his RCA recording of German opera arias and

an Act 2 concert in Geneva with the same conductor he ended doing

Tristan with. How deeply does one get into the text of an opera such

as Tristan when preparing for the role?

"Well, you translate

it if you don't understand it already. And then you read some background

material. I'm not the type that spends months and months learning

about each particular word. I learned about the philosophical background

to Tristan - with Wagner and Schopenhauer and various types of philosophical

influences - you know, where did that come from and all that.

But ultimately once you sort of get enough to feel like you've got

your ideas around it, if you get that much more, I don't know that

that comes out. Because a lot of what comes out is a feeling from

inside. On my part, it's not an intellectual exercise, it's an emotional

exercise. I don't spend as much time as some might do in finding out

all the background because I find that all that starts to come out

as you begin to feel and understand the words and the text through

the music."

Tristan und

Isolde is of course what Wagner himself described as his "monument

to this most beautiful of dreams in which love will be properly sated

from beginning to end." It's a 4- or 5-hour opera that's so intense,

very passionate, that it wouldn't be hard to imagine that a singer

would feel emotionally drained after a performance. Heppner says:

"Yes and no. My sense

is, you look through all the emotions for the character. You work

through that in your learning process and in rehearsal. But if you

are completely wracked with the same emotions while you are singing,

you are not going to be able to finish the piece. I mean, think about

having to give a speech at the funeral of your mother. You are filled

with all these conflicting emotions You might be able to go through

it, but you probably will have to stop and your voice will break,

and you'll cry. You can't allow that to happen while you're singing.

You'll have to remain a little bit at arms-length from those emotions.

"However

that's not to mean that we have not experienced them en route there.

My feeling is... if you ever read Robertson Davis, the Canadian author

- he wrote 'The Deptford Trilogy' and there's one in which they produce

an opera where he talks about the fact that you need to experience

those emotions. And then at

each performance,

you need to do the same thing that

got you to experience those emotions

- and it's the audience who gets it, not the performer. Because during

a performance, it's not the performer who needs to feel it, it's the

audience. So that's what I'm trying to work toward - to get them to

feel those emotions and also to maintain the ability to sing."

Ben Heppner's most recent

portrayal of Tristan, with Waltraud Meier as Isolde, was at the Opera

Bastille in Paris. Originally presented in a semi-staged concert

version at the Disney Hall in Los Angeles with Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

the LA Philharmonic, it is the most unconventional of all the productions

of the opera to date. It is Peter Sellars' multi-media vision

in which technology - via a giant screen of images by video artist

Bill Viola, running in parallel to the action on stage - plays an

overtly dominant role equal at least to the singers on stage and the

orchestra in the pit. Tristan and Isolde - welcome to the 21st century!

One wonders: if Wagner were alive today, would he have approved of

it as an element of Gesamtkunstwerk? Perhaps. Here's Heppner's

take on the production:

" I thought we got

a lot of good things on the go' but I thought that in the first act,

the Bill Viola video - and I love them- was telling a different story

than we were telling. Different, not better or worse, but it

wasn't the same story. And then during Acts 2 and 3, things started

to finally gel a little bit. Particularly in Act 3, it seemed the

less specific the images were on the video, the more it related to

our telling of the story. So I thought that Act 3 was the most successful

- with the colors and the images of water that he used, the color

filters, light going through and running backwards, or upside down

or both, and the image at the end, although some people thought that

was kitschy. But I loved the ascension of Tristan into the heavens,

I thought that was just gorgeous."

He has fond memories of his first Tristan

in 1998, with Jane Eaglen as Isolde:

"I kind of like the

first one I did, which was in Seattle. It had its moments too. I thought

Francesca Zambello did a great job of drawing a good character for

me. She had certainly done her homework, was very encouraging

and helpful in eliciting a good characterization."

He has performed Tristan with Deborah

Polaski as well, but with Jane Eaglen more times than with anybody

else. He has sung the role on the concert stage - in Ottawa, Montreal,

Cincinnati, and most recently at Lincoln Center in the Fall of '05

- all with Deborah Voigt with whom he has made recordings of complete

operas by Beethoven, Strauss, Wagner, and Weber as well as performed

in productions of Lohengrin, Oberon and Les Troyens.

So, does the world's leading Heldentenor have a favorite leading lady?

Of course, he won't tell even if he had one, and if asked, one would

expect him to say - which he did: "My

favorite's the one that I'm working with."

back

to TOP

OTELLO

OTELLO

The

Wagnerian is a Verdian too, certain to inherit "ownership"

of Otello from the role's erstwhile consummate owner, tenor Placido

Domingo.

Having sung it first with Renée Fleming in the role of Desdemona

at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 2001 [(Photo

Credit: Robert Cahen, with permission of Mr. Heppner], Heppner

has since performed Otello at the Metropolitan Opera and Covent Garden.

Many more reprisals of the role surely can be expected in the years

to come.

THERE'S MORE WAGNER

ON THE HORIZON!

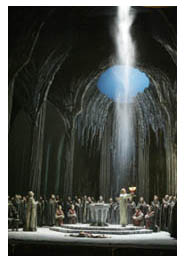

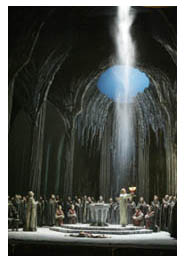

PARSIFAL

Lohengrin,

without question, foreshadowed Parsifal. Yet

more than 30 years separated Wagner's completion of the two works.

It has been many years too since Heppner first sang Lohengrin (in

1989), but his fans won't have to wait 30 years before they see him

as Parsifal. He will debut the role at the Metropolitan Opera in May

2006 under the baton of James Levine in a traditional production by

Otto Schenck (photo

at right: courtesy, Metropolitan Opera). It may

not have taken 30 years, but did he have to wait half that long to

sing the role? The answer came up unexpectedly during a discussion

of if and when he would sing the role of Siegmund in

Die Walküre. Here's what he said: Lohengrin,

without question, foreshadowed Parsifal. Yet

more than 30 years separated Wagner's completion of the two works.

It has been many years too since Heppner first sang Lohengrin (in

1989), but his fans won't have to wait 30 years before they see him

as Parsifal. He will debut the role at the Metropolitan Opera in May

2006 under the baton of James Levine in a traditional production by

Otto Schenck (photo

at right: courtesy, Metropolitan Opera). It may

not have taken 30 years, but did he have to wait half that long to

sing the role? The answer came up unexpectedly during a discussion

of if and when he would sing the role of Siegmund in

Die Walküre. Here's what he said:

"It would happen, but it's not booked

in yet. It's certainly a good thing for me. But I have avoided

it - Siegmund and Parsifal I have

avoided because they were a little bit too low for me. Many Heldentenors

come from the baritone side. And when one moves up into the tenor

repertoire, the easiest thing to start with for somebody who is a

baritone is Parsifal, and then Siegmund.

But for me, because I was already on the top end, I decided I should

spend more time at the higher end of things rather than try to make

my voice get deeper. That would happen with age, anyway."

For Ben Heppner, Parsifal has finally come of age, and Siegmund, we

can expect, shall not be very far behind.

SIEGFRIED - the role everyone's been waiting for

He has sung excerpts from Wagner's Siegfried

and Götterdämmerung in

concert and on record, but has never performed the role of

Siegfried in a fully staged production. But the opera-going

public has always known that it is only a matter of time. The time

is nigh! In January 2005, it was announced that Ben Heppner will perform

the role of Siegfried for

the first time in a new production of Wagner's Ring cycle at France's

Aix-en-Provence Festival, appearing in the cycle's third opera

Siegfried on June 28, 2024 and in the fourth

opera Götterdämmerung on July

3, 2009. Meanwhile, he's warming up to the role...

"... slowly. I've been working on a

recording. I would have finished it already, but I got a cold and

got stuck. But I'm doing some of the solo sections of Siegfried

and I've been doing a duet section with Debbie, and I've got an Act

3 next year in concert - in Manchester, I think. So, I'm sort of trying

to fill it in and get it into my voice. Particularly important is

that Act 1, because the Schmelzlied and the Schmiedelied

- the Heldenhammer song, the forging song - are so demanding of the

physical and vocal qualities that you need to get it worked in very

early."

And is it more demanding than Tristan?

"Oh yes. And I won't know it until

I've sung it 3 or 4 times in a row. In studio, it's not the same as

when you're just doing it in your practice. And on stage, Tristan

for example is a totally different opera than when you're rehearsing

it alone. I'm

trying to learn the music. I mean it's all part of the development

process, but the rehearsals leading into it are another level.

You get a different sense of physicality there than you do in concert

where

you don't have to do the acting.

There's something that's much more demanding when you're in costume

and in character from beginning to the end."

If there's a tenor

who might be "envious" of Ben Heppner today, it could be Placido Domingo

who, much as he wished it, has not been able to add Tristan

and Siegfried to his tenor repertoire of over 120

roles in staged productions. He has of course just released a much-acclaimed

studio recording of the complete Tristan, fully accepting that it

is not among his many good fortunes to sing the role in a fully staged

opera.

"I don't know that

he could have done that, I'm not sure. Because it is a different type

of singing than Placido ever did - in terms of the length of it. I

can't think of another role in Italian that compares to it, I just

can't. And Otello isn't even the same, because it's very short comparatively.

And all the other big Italian things, I don't know if there's anything

that really compares with Tristan. And Siegfried

I can't even speak authoritatively about. Those people who have sung

both Tristan and Siegfried, and

perhaps Tannhäuser as well, maybe can speak

more authoritatively about which one's more difficult. And... that

is somewhat colored by - is it more difficult for them, their particular

voice? I find Tristan more difficult, or maybe you

might find Siegfried more difficult. it depends

upon your voice, probably."

back

to TOP

ABOUT THE

TENOR VOICE

Take it from a Heldentenor:

"The tenor range

is very much more precarious. We seem to have higher voices,

but really, we don't; it's just that we learn to sing up there. And

it's very much more precarious than singing as a baritone."

Like always climbing

Mt. Everest?

"Yes! And slipping

off the edge at any given moment."

Like most careers

that have risen from high voices, Heppner's has had some ups and downs.

But given where he is now - at the top of the world - it

is obvious that Heppner has heroically mastered the Heldentenor's

art of living dangerously.

RECITALS: I like the direct connect with the audience.

Heppner

has not ignored the recital/concert track of his career even as he

takes on these big demanding tenor roles. His collaborator 80-85%

of the time is pianist Craig Rutenberg. Heppner

has not ignored the recital/concert track of his career even as he

takes on these big demanding tenor roles. His collaborator 80-85%

of the time is pianist Craig Rutenberg.

"Last year, I counted

13 recitals. This year I've only got three. So this is not my recital

year, but the following year, maybe we get a little bit more. I like

the recitals... I like the direct connect with the audience - the

repertoire can be more varied, and I can get to more places in less

time."

And what about the kind of adrenaline rush one feels when singing

in recital as compared to opera?

"Oh, they are different

things. But I probably get more during a recital because you don't

have anybody to hide behind. In an opera, I've got somebody else to

take the other side of the duet, or somebody else is doing their aria

while you are offstage, or at least not singing. So, in a recital

the responsibility is all yours, and in that sense the pressure is

greater. But you can schedule and plan a good set of pieces to begin

with, and then maybe get into the meat of the program at the end of

the first half and the beginning of the second. My routine is always

to find a set of songs at the end of the recital that people relate

to, so that they can sort of feel that they can sing those songs too."

[Photo © Marco Borggreve, with

permission of Mr. Heppner]

All these songs and operatic arias are more often than not sung in

a language other than Heppner's own Canadian English. When asked if

he had a natural facility with languages, he gave a reply that elicited

laughter:

"Uhmmm - imitation!

I'm OK in German but not fantastically fabulous, my French seems to

have gotten worse than better, and I seem to have forgotten my Italian

conversation," adding

that he can still sing German better than he can speak it. "But

I'm OK."

Guess

who's at the top of his list of favorite composers. Wagner, of course,

is the easy answer given his repertoire. But guess again...

"Well, musically

I tend to think the late Romantic period is the kind of music I relate

to the most. Mahler would certainly fit in it, Wagner of course. And

Strauss. But if there was one composer that I wish had written more,

it's Mahler - because I love his music. He didn't write any operas,

and only a very limited number of songs - I've not done any, not publicly.

Das Lied von der Erde, yes, I do that a lot. And I do the

Mahler 8th.

"Of course I know Wagner is a natural fit for me, and sort of

the other side of Wagner would be someone like Brahms. But I love

the writing that Mahler did. Most of the songs that he had written

are really suited for darker voices - mezzos and basses. But I love

the music, I love the symphonies. This type, this whole Romantic period

- it feels right for me. I have a daughter who actually is a classically

trained pianist with a degree, and she and I agree that Beethoven

is early music... rather than Monteverdi and Palestrina."

MUSIC AND THE HEPPNER FAMILY

And

laughing heartily at that "Heppnerian" reclassification

of the chronology of Western Music, we briefly got sidetracked into

a discussion of music and the Heppner family. "Now that you have

a daughter who's a classically trained pianist," we asked, "Could

one look forward to a father-daughter performance sometime in the

future?" He answered, quite confidently: And

laughing heartily at that "Heppnerian" reclassification

of the chronology of Western Music, we briefly got sidetracked into

a discussion of music and the Heppner family. "Now that you have

a daughter who's a classically trained pianist," we asked, "Could

one look forward to a father-daughter performance sometime in the

future?" He answered, quite confidently:

"No, no. There won't be. No. I don't know that she'll actually

make her living in the long term as a classical pianist. She's actually

in Europe now - in the Ukraine doing sort of humanitarian, church-related

work."

[Photo © Kasskara, with permission

of Mr. Heppner]

And as to whether there was anyone else in the family who is musical:

"Well, yes.

Kind of amusingly so. My boys - I have two boys, and they're both

very musical. Both my boys play guitar. And my older boy who's 21

plays banjo. It's interesting- he's actually studying philosophy.

He's not in music, but it's a great passion, and it's an avocation

for him. He got a banjo one Christmas, and he worked at it. He also

sings along as he plays. He doesn't do the Tamino and Papageno kind

of stuff. He does some Woody Guthrie, and Robert Johnson and all the

old blues and folk people from fifty or seventy years ago. He went

for a different kind of summer job this year. He decided to be a busker

on the streets of Toronto - a street musician. So, he mapped out a

strategy and worked 5 or 6 hours a day - part of it at this market

and part of it at this other corner, and he actually did better than

if he had worked at a regular job like a regular student does, certainly

better than at McDonalds, and better than at other jobs. My wife is

also musical; she's a trained pianist as well. "

That does not necessarily mean his son won't go into opera, we interjected,

citing the real-life example of the Relyea family (Canadian opera

singer Gary Relyea whose son John Relyea, one of the finest bass-baritones

among today's young opera singers, was set on becoming a rock band

artist before he turned his sights to opera).

"Oh, I don't

think you'll be hearing about that in our house," Heppner

disagreed, with a high degree of parental certainty.

"He assiduously avoids getting into this opera thing. I don't

think my boys will change. But they are very musical. All my kids

are musical."

The question of balancing family life with a celebrity career in opera

is frequently asked of opera singers, but more often of the women

than the men - which makes one wonder if it's more a "woman thing."

This is how Heppner, who has made Toronto his home since moving there

from his native British Columbia to go to opera school, looks at it:

"Quite frankly,

it's a lot easier for a husband and father to be able to have a career

and raise children. Really, I have to say the big award in consistency

and effort belongs to my wife. She stayed with the kids. We decided

to center ourselves in one place and that I would come back to their

world rather than them always coming with me, although they certainly

did that numbers of times. But, I limit the amount of weeks I'm away

from home, and try to come home as frequently as I can. For example

when I'm in New York and I get two days off, I try to come home rather

than stay all the time in New York."

back

to TOP

OF CRITICS and YOUNG SINGERS: Who has

earned a right to speak into your life?

Swinging back to his career, we inquired as to the kind of feedback

he uses - critics' reviews, audience reaction, etc. His reply, though

not surprising as performing artists go, was quite interesting in

that it somehow led quite naturally to a summary of his advice to

young singers:

"You know, critics

have their own point of view. And I don't know what it is. They're

not known entities to me. Some of them are very good, but you just

don't know. I admire good critics. And I do read them - for other

things, but for things that I'm not in. I really appreciate

the perspectives of some of them. But if I live my life trying

to find out what they think, I'm going to have emotions that are obscene...

I'm going to be an emotional wreck. So... and I tell young singers

this:

"What you need to do is to figure out who has earned the right

to speak into your life. If you're married, your spouse automatically

has the right; your teacher, your manager, certain friends and those

others who have earned the right and whom you understand as having

an insight. And I don't mean they need to be trained musicians; they

need to just have a really good way of analysis.

"For example, my wife is a pianist, but she's got a great sense

of what it takes, and what she wants to hear that are beyond musical

things. And you'll find other people who have very little musical

training who are very sensitive to this kind of thing. And if you

happen to know one and you're lucky enough to have one in your life,

LISTEN! They don't have to be musicians. It saves you from having

to run to this new person - as when, say, you're training as an opera

singer or you're singing in the chorus, and in comes some big name

and half of the chorus sort of run to that person. They want advice,

they want this and they want that. I say, you know what? He

or she has not earned a right to speak into your life. Why don't you

just take away from them what you can. If you are lucky enough, don't

go searching for it. Otherwise, you're going to be double-minded all

the time. And as they say, a double-minded man is unstable in all

his ways. You need to believe in yourself and not run to every new

person as being perhaps the key to unlocking your career. You have

the key to unlock your career."

Thus, one gets the sense that Ben Heppner does care about giving young

singers a chance, mindful perhaps of his own climb to "the top

of Mt. Everest." In addition to giving up Die Meistersinger

because it's time to hand the role over to younger singers ("They've

got to have some stuff too.")...

"I usually

turn down Beethoven 9th, because generally you don't get to do very

much in it. It's hard and unrewarding, and they have to pay me a lot

of money to do it. So, I think they can probably do just as well by

hiring an up and coming young singer for that particular role. I mean,

if it's a very important conductor, a recording or something, yes,

I'd probably do it. But after having done it once, you do it

a few more times, and then you say... somebody else can do this."

NORTH AMERICAN SINGERS

ASCENDANT

And so, with Ben

Heppner (and of course Renee Fleming, Deborah Voigt, Denyce Graves,

Susan Graham to name some names) having taken center stage in the

opera world, and with many younger singers waiting in the wings, it

appears that opera has entered a new era in which North American singers

are truly ascendant. Heppner agrees, with a minor reservation:

"That's a fairly generalized

statement. But yes, I think there's a fairly strong influence there.

Although if you look back, you had Richard Tucker, Rise Stevens, Jon

Vickers in huge international careers and there are many, many more

North American singers whose names just haven't come to mind at the

moment. There's really solid training in America right now. Not only

are they good singers, they have good musicianship, they are good

actors and so well-rounded. I think it's quite natural that the good

singers are going to rise."

What

does Ben Heppner see when he looks at his crystal ball? Is it

his goal to sing even half as many roles as Placido Domingo has sung,

for example? He laughs as he replies with characteristic modesty:

"Noooo!

I could never do that. He started much earlier, and he sang much more

often. No. The goal that I have in mind for me is to have a handful

of roles that people want to hear me sing, to be sort of the No.1

phone call for a handful of roles, let's say, five or six. It's not

a sense of being smart on my part or being wise. It's a matter of

not needing or wanting to let the career completely take over the

rest of my life. "Noooo!

I could never do that. He started much earlier, and he sang much more

often. No. The goal that I have in mind for me is to have a handful

of roles that people want to hear me sing, to be sort of the No.1

phone call for a handful of roles, let's say, five or six. It's not

a sense of being smart on my part or being wise. It's a matter of

not needing or wanting to let the career completely take over the

rest of my life.

"And I could never compete with somebody with the talent or ability

of somebody like Placido who - talk about an all-around musician and

opera singer - he really is a model for everybody. He sings beautifully,

he's a good actor, he's a great musician, he's got all these things

going. He is so amazing at all of those things, even conducting he's

doing very well. And anybody else who is that way owes a debt of gratitude

to Placido." [Photo

© Marco Borggreve, with permission of Mr. Heppner]

With Tristan

and Siegfried and all the other heavy roles already

in his pocket, Ben Heppner doesn't really have to wish for much more.

"Plus," we asked him, referring now to his new found hobby,

"You want to spend some of the time motorcycling, don't you?"

"I still have a slight impediment to doing that. My wife is so

nervous about it. She gets so uncomfortable."

"That's

what we figured. But you know what? We think you'd really look great

on a Harley."

"I'm working at it!"

And on that happy

and hopeful note, we said goodbye, best wishes, and many thanks for

what turned out to be a long but most pleasant, informative and refreshing

conversation.

back

to TOP

|

That was in the mid '70s and early '80s, when he began to grasp what

opera is all about.

That was in the mid '70s and early '80s, when he began to grasp what

opera is all about.  Die

Meistersinger is easily the most listener-friendly of Wagner's

operas, certainly his brightest and happiest (nobody dies in the end!).

The vehicle of Heppner's La Scala debut in 1990, it became his first

calling card. Today, after having sung the role innumerable times

in concert and staged performances on both sides of the Atlantic,

he has decided to say goodbye to the role, for reasons that interestingly

have nothing to do with singing.

Die

Meistersinger is easily the most listener-friendly of Wagner's

operas, certainly his brightest and happiest (nobody dies in the end!).

The vehicle of Heppner's La Scala debut in 1990, it became his first

calling card. Today, after having sung the role innumerable times

in concert and staged performances on both sides of the Atlantic,

he has decided to say goodbye to the role, for reasons that interestingly

have nothing to do with singing. PETER

GRIMES

PETER

GRIMES

Lohengrin,

without question, foreshadowed Parsifal. Yet

more than 30 years separated Wagner's completion of the two works.

It has been many years too since Heppner first sang Lohengrin (in

1989), but his fans won't have to wait 30 years before they see him

as Parsifal. He will debut the role at the Metropolitan Opera in May

2006 under the baton of James Levine in a traditional production by

Otto Schenck

Lohengrin,

without question, foreshadowed Parsifal. Yet

more than 30 years separated Wagner's completion of the two works.

It has been many years too since Heppner first sang Lohengrin (in

1989), but his fans won't have to wait 30 years before they see him

as Parsifal. He will debut the role at the Metropolitan Opera in May

2006 under the baton of James Levine in a traditional production by

Otto Schenck  Heppner

has not ignored the recital/concert track of his career even as he

takes on these big demanding tenor roles. His collaborator 80-85%

of the time is pianist Craig Rutenberg.

Heppner

has not ignored the recital/concert track of his career even as he

takes on these big demanding tenor roles. His collaborator 80-85%

of the time is pianist Craig Rutenberg. And

laughing heartily at that "Heppnerian" reclassification

of the chronology of Western Music, we briefly got sidetracked into

a discussion of music and the Heppner family. "Now that you have

a daughter who's a classically trained pianist," we asked, "Could

one look forward to a father-daughter performance sometime in the

future?" He answered, quite confidently:

And

laughing heartily at that "Heppnerian" reclassification

of the chronology of Western Music, we briefly got sidetracked into

a discussion of music and the Heppner family. "Now that you have

a daughter who's a classically trained pianist," we asked, "Could

one look forward to a father-daughter performance sometime in the

future?" He answered, quite confidently: "Noooo!

I could never do that. He started much earlier, and he sang much more

often. No. The goal that I have in mind for me is to have a handful

of roles that people want to hear me sing, to be sort of the No.1

phone call for a handful of roles, let's say, five or six. It's not

a sense of being smart on my part or being wise. It's a matter of

not needing or wanting to let the career completely take over the

rest of my life.

"Noooo!

I could never do that. He started much earlier, and he sang much more

often. No. The goal that I have in mind for me is to have a handful

of roles that people want to hear me sing, to be sort of the No.1

phone call for a handful of roles, let's say, five or six. It's not

a sense of being smart on my part or being wise. It's a matter of

not needing or wanting to let the career completely take over the

rest of my life.