|

|

| Building THE ELLIE | LOBBY | MAIN HALL | OTHER SPACES | OPENING NIGHT | The STARS | MOVERS & SHAKERS | CARMEN |

| THE ELLIE CAULKINS OPERA HOUSE: PETER LUCKING, Meisterarchitekt |

MOVERS & SHAKERS SUSAN & JEREMY SHAMOS ELLIE CAULKINS PETER RUSSELL JAMES ROBINSON PETER LUCKING ROBERT MAHONEY MAYOR HICKENLOOPER JACK FINLAW CHRIS WINEMAN MARC SCORCA USA UK DE FR AUDIOFILES NEW RELEASES FOOD & MUSIC SITE MAP

|

||||||

|

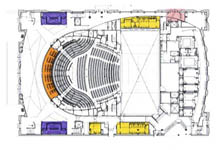

Photos credits: Semple Brown, Wonder Works Studio, KKN Enterprises, FanFaire If you stand on the corner of 14th and Champa Streets in Denver, facing the neoclassic historic building that is literally the cornerstone of Denver's performing arts complex, and then walk a few steps through its doors into the thoroughly modern, elegant interior, you cannot but believe that it will. As we did, over The Ellie's grand opening weekend in September 2005. If you hear Peter Lucking's first-hand story about the building of The Ellie, you'll come out thoroughly convinced that it will. As we were a few weeks later, following a phone interview that was enjoyable, informative, and educational. Peter Lucking took us from the concept stage all the way to opening night and a bit beyond. We learned that Semple Brown Design had somewhat of a headstart on the building project which was approved by the citizens of Denver in 2002: "We actually did have some basic design ideas because we helped with the amendment that was put on the ballot. We did some very early concepts of what it would look like - the general plan- and how it would work. And so we did have a headstart, a jumpstart on the design, having worked with the city for a number of years on programming the building. But, basically, a year was what we spent in design."

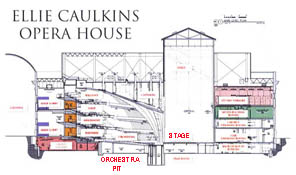

LIKE BUILDING A SHIP IN A BOTTLE: "MORE CHALLENGING THAN BUILDING FROM THE GROUND UP" Because the opera house was to be built inside a pre-existing structure, the project was likened to "building a ship in a bottle." But demolition of the interior was the first order of the day, a process that lasted 6 months. As Lucking tells it, it was done, by necessity, in a very orderly fashion by the contractors, PCL Construction, and involved an amazingly small crew. Lucking and his team were always there. "Our team and structural engineers were continually on site because of the historic nature of the facade and the existing structure which could collapse anytime. So it was very delicately done. We also had to have an asbestos abatement. To tear it down, they actually did most of it by hand, believe it or not, with very small equipment. It involved a very small crew of probably about 30 people. The real key was the equipment they brought in, which was like a dinosaur - very long neck with crocodile teeth at the end. It was remotely-controlled, and it really just ate the building."

No one involved with the building of The Ellie had known of the sandstone because it was totally covered up during the previous renovation (in 1955) with a dark wall. That sandstone is the existing rubble foundation. "We had it very carefully cleaned, hand-washed basically." It turned out to be the perfect background for the artworks by Denver artist Vance Kirkland that now hang in the Salon. The paintings and the costumes on display in the Salon give the place a feeling of the arts, said Lucking. "It's very difficult for people to go down into a basement area, so the space had to feel very special." Photo © 2005 FanFaire But would Lucking have preferred to have built the Opera House completely from the ground up, both exterior and interior? Surely an architect showcasing his works would rather say 'I did that building!' instead of 'I did the inside of that building." "That's a very hard question," Lucking replied. "But this was actually a lot more challenging than building from the ground up. And I think that the historic building has a wonderful harmony with the new work. There is something to be said about a historic building. There's a great sense of arrival and history in having the outer facade of that building and I really think that it actually added to the project. You feel that you've arrived."

More than a lighting fixture, the gold-and-green chandelier is a glass sculpture that, like all Chihuly installations, invites conversation. "Naturally there were some concerns about where we were going to put it. But we took a good look at that location in the center of the lobby, and saw that the chandelier was the appropriate place for it. It's not too big to overpower the lobby, but it's a really nice piece that adds a nice, beautiful warmth to the space." A most welcome addition to the lobby, the chandelier was not commissioned expressly for The Ellie - in fact, there was no budget for one! "What's quite amazing is how well it fits!" Lucking loves to point out that the lobby gives little hints of what one is going to see in the main hall. "If you look in the lobby, for example, the whole design comes from the center of the house. And so we wanted to also have a piece at the very center of the house." He is referring of course to the Estey chandelier in the main hall. "A lot of people think our chandelier drops down and opens up because they have one at the Met that does that. It has nothing to do with the Met. Traditionally, the opera houses in Europe were lit with candles. Prior to a show, they would light the candles. And the chandelier would be raised up into the dome to blow out the candles, which was why it went up and down. It's really a little bit like a tiara, where the lights are like the diamonds that are slowly coming out to a necklace. We started calling them snowflakes. In the lobby you see these little echoes of snowflakes that eventually, when you come into the house, are the center snowflake. And it was Teal Brogden and Sarah Brown and myself who sort of came out with this idea that gelled into this wonderful chandelier that opens and closes. "It's

a centerpiece. And I think those who design opera houses often forget

that people are there for an event. The house has to be that event

the night you arrive, and there has to be something that tells you

the show is beginning. I think it's a very elegant way to say that,

and it follows in the great tradition of the grand opera houses in

Europe." But of course people come to the opera not to marvel at chandeliers but to experience a special art form that is both aural and visual. If the goal was to build an opera house that would rank among the top 10 in the world, the real challenge for Lucking and his team was to design a hall in which acoustics and sightlines are engineered to perfection. Was the mission accomplished? A resounding YES, based on the overwhelmingly positive audience reaction on opening night, music critics included. How did Lucking and team do it? Lucking gives a lot of credit to acoustics consultant Robert Mahoney. "I've worked with Bob for many years. He was with us all the way through the design. Having him in Boulder was wonderful because we met weekly, and sometimes twice weekly. "One of the first things we did when we sat down was say we want great acoustics, but what does that actually mean in design? I really think the key to a great house and its longevity is about the sight of the stage - if you can see it well, you can hear it well. Our sightlines are really designed to the orchestra pit, so that you can see the conductor. If you can see the conductor and the orchestra, you can hear them better. That really means having balconies that are not deep, that have a height to depth ratio of 1 to 1.1. Acoustically this ratio is very, very critical." But was there ever an instance when sightline had to be compromised for sound, or vice-versa? "No. There was never really an instance when we had to do any compromises, except perhaps on the upper balcony where we discovered that the actual historic roof trusses were not at all as we were expecting. We actually had a raised barstool fit up there so that the ceiling does not hit you in the head. But we did not compromise acoustics or sightlines." The Ellie is often referred to as Denver's lyric jewel. Lyric as pertaining to song, one assumes. Not until one sees the configuration of the main hall does one realize that LYRIC, in fact, refers to lyre, the musical instrument, or more specifically, its shape. "Yes, it really refers to the lyre shape," Lucking concurs. "It is an expanded versus a narrow lyre. But it is definitely a lyre shape."

As one enters the hall, the eyes are drawn to the circular maze of wooden panels on the ceiling as well as the panels on side walls. It was our guess that they were put there for an acoustical as well as an aesthetic reason. "Yes, they're designed for both. It was very easy to conceptualize how it would look visually inside, and really the side walls are doing what the classical columns and the classical royal box would do in a classical opera house - which is link the ceiling and bring your eye to the stage. So, the form of the house with the sidebox pulls your eye forward and then the sweeping nature of those elements pulls your eye down. "In the ceiling the center piece around the chandelier is an echo of the classic domes that you would find in opera houses.The horseshoe that reflects around that is to pull your eye forward and also to sort of play back on the horseshoe itself, and the acoustic reflectors up in the proscenium zone complete the piece. The difficulty was the shape of it, and Bob Mahoney had to work very hard - with Eric Bowman in our office - to continuously look at these in order to get the right shape because they are curved in all directions. It's not apparent when you look at them, but they are very complex shapes." What about the Figaro seatback titling system, was it in from the very start of the design work? "No, it wasn't. It's funny because Jack Finlaw came one day and said, 'By the way, we're going to put Figaro in the house.' I said, 'I'm sure Figaro will play here some time.' 'No, I'm talking about Figaro.' 'What are you talking about?' I asked. He said, 'The text system.' "Initially I didn't know what it was. And personally, I wasn't really sure it was a very good idea. When I was shown a sample and some pictures of the work they had been doing in La Scala and also in Santa Fe, I was still nervous, because we had a seat with a reclining back, and I wasn't sure how we were going to design this piece in. But luckily, we came out with a very nice solution. And it's actually unique. It was designed into the headreast so it 'looks like it's always been part of that seat and designed as a headrest, but actually it was not designed originally this way. So in the end, Lucking was convinced that Figaro works. "I think it even accentuates the lines of the house." AN ORCHESTRA PIT LIKE NO OTHER At The Ellie, the orchestra pit is not "the pits." Special acoustical features were incorporated into its design, of which Lucking and Mahoney are quite proud of. " Yes, our orchestra pit is fairly unique, I don't know if you realized this. We have the standard double lifts that everybody has. Then we have the acoustic walls that are very solid that raise and lower to reflect the sound back at the performer and also protect the first few rows of the audience so they are not overpowered by sound. But in addition to that, the rear wall of the orchestra pit is movable. It is actually an acoustical winger shell piece that moves on wheels in and out to push more sound out of the orchestra pit or to reduce the amount of sound, depending on how the sound is through to be perceived by the audience. " In other words, the movable back wall works just like the lid of a grand piano, you open it and you hear it louder, and if you want to temper the sound, you close it a little bit more. This orchestra pit is like no other in the world today. "And that's because of the walls that move up and down on the orchestra lift. They were made movable so that the change-over times are reduced - the amounts of time and effort. In addition, all the seats are on wagons. Normally when you change a seat wagon, you'd have to put in temporary handrails and all sorts of things. These walls do all of that for you. And it means that the quality of the visual look is a lot better. But it is the first in the world like that. And I hope it will catch on. I don't really know why nobody else has done it before." But there's even more: "The floor level is adjustable. So, if you had a very large orchestra in there, say, 110 musicians which we can accomodate, we would set both lifts before the stage lit to bring the orchestra higher up and out into the house. Obviously, if you wanted to create a Wagnerian pit, because we have a movable back wall, you could use only one lift and the 110 musicians go underneath the stage in the trapped area. That's the reason for having the movable walls - so that the area can be used as a full trap or as a full orchestra pit. So, there's a number of combinations there. "The finishes in the orchestra pit are likewise adjustable. On one side of our adjustable platform is carpet, which gives us the ability to deaden the sound, on the other side is a hard surface, so we can adjust the amounts of sound coming out in that manner. So far, we've discovered that we prefer it with the hard surface. These things are really sort of tested to see it. But the hard surface seems to be working better to get the sound out of the orchestra pit and the musicians seem to prefer it too." A STAGE DESIGNED FOR THE SPECIAL NEEDS OF OPERA "A lot of houses are limited by the height of the proscenium. The other good thing about having a high proscenium as we do in The Ellie is that more of the sound on stage can come into the audience. As the audience are vertically stacked in an opera house, the height of the proscenium becomes very very important because visually you want the audience to feel part of the stage. A very low proscenium hinders that feeling - because the balcony can't sweep around, the side box doesn't come in into the proscenium and make the audience feel as if it's comfortable." Diagram courtesy: Semple Brown Design Lucking also made of point of the fact that the floor can be opened at any point on the performance stage. "That's any point between where the performers would actually perform. And it's fully trapped. It's a traditional cat trap, but it's designed with modern materials. Also, lightweight truss systems support the floor and the reason for that is so it doesn't squeak." Even the curtains were engineered, so to speak. "I don't know if you realized it, but they're very unusual. The color was our choice. The curtains are very light weight. Normally they're very heavy, but Bob Mahoney, said 'You know, Pete, we really have to watch the weight of these curtains because they're going to absorb a lot of sound. So, the material is actually man-made fiber, of the velour option for Colorado because of our dryness here. It's actually a 16-oz velour instead of normally a 24- or 25-oz. All the draperies on the stage are light weight and the reason for that is NOT to absorb sound, to push as much of it out as we can." DRESSING ROOMS DESIGNED

TO PAMPER THE STARS "I really think the other part of the design that's often forgotten are the dressing rooms," Lucking explained. A lot of people, when they're designing, forget about the performers. At The Ellie, the dressing rooms are really about them. You know, the audience is there for only 3 hours. The performers are there all the time, for many hours, taping the show, going through rehearsals... We need to pamper them, because the reason we come to these performances is to see them. We need to remember they are the stars and make sure they feel like a star. I think they give their best performance when they are pampered too. But it's also saying to them "You are important." Then, there's the humidification system which was installed to control the humidity not only in the dressing rooms but in the entire house as well, to make it comfortable for everybody - the performers and the audience. "The hall, the stage and the dressing rooms are all humidified so the voice doesn't dry out. Normally, here, when you're talking in front of an audience you'll last about 5 minutes before you have to have a glass of water. The humidity is actually set pretty constantly at 45%, which is the ideal humidity for voice and for instruments." Lucking also suggests that controlling the humidity might make a very big difference architecturally to the materials in the house. Obviously, Lucking and his team spared no detail and left almost nothing to chance to make it really easy for a company to produce an opera and for performers to give of their best. AND SO, ON OPENING NIGHT... During the interview, which took place while rehearsals for the season opener Carmen were about to begin, Lucking looked back on what did not happen on opening night. "Normally, you have time to test before you open. But that didn't happen here. One of the difficulties of designing a house like this is that there are so many unknowns - from the seats that you put in to the stage sets. Sets make a huge difference. SAnd one of the things about The Ellie Caulkins Gala night was there really wasn't a stage set. "We

had several mistakes. But now we're

very excited because there are sets on the stage and I think we're

going to find out very quickly if it works or not. The sets for Carmen

by the way are fantastic - a very traditional raked stage, the burnt

theatre in the background with the proscenium - it was really quite

amazing to see those. I think we will be doing some adjustments to

the house, but first we want to watch out for what happens during

all kinds of performances in the house. Right now we feel that the

acoustics are very good. There are some areas that need some improvements,

but they're minor." But the important thing is - Peter Lucking went home after the opening night concert one very happy architect. "I was very happy. My whole team did an amazing job. It really has taken a team, you know. I stand in the pit as the conductor of my team - and there are so many people who worked very very hard on this project. We really had ownership of this. Our whole firm has worked together to create this. All our families were part of this too - without their support we never could have achieved this in such a short period of time." back

to TOP

"I wanted to be an architect when I was 11 years old. That was the time I realized I wanted to be an architect. My parents had always taken me to Europe in the summer and we toured the great buildings of Europe. And I think it was just a passion. I saw so many buildings that I thought 'Maybe I could do that.'" Among the architects whose works he admires are Alvar Aalto, the internationalist architect from Finland and the Chicago-based American architect Dankmar Adler who designed many theaters. How Lucking ended up designing theaters is a long story, but "The short version is - I was working for an Italian firm in the Middle East and looking for an interior lighting consultant. I couldn't find one architecturally who liked this palace that we were designing for the Emir of Qatar. So we found a theater consultant - because I regarded the palace as a big stage set - Richard Pilbrow from Theatre Projects Consultants. That's where I first met him, and when I finished the design, he said 'What are you doing?' and I said, 'Well, actually I'm not really doing anything. I don't want to go back to the Middle East.' And he said, "Why don't you come and work with me? Actually, he wasn't in the US right then. But basically I ended up working with him in the US doing consulting to other architects. So we would go around consulting on theaters. I knew nothing about theaters and I learned everything I know about theaters. I've been working on theaters for about 20 years." Among the well-known theaters he has worked on while a consultant with Theatre Projects is Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. "We were very lucky to work with Frank Gehry, a wonderful architect with a wonderful team, on the design of that space. Obviously Frank is a great designer and he took the lead role but we did our part to support it." And it was while consulting on the Ahmanson Theater project, also in Los Angeles, that he first met acoustician Robert Mahoney. "So, now you know everything about theaters," we asserted. Ever the modest man, Lucking said "Oh, you can never know everything." In

1996, he joined Semple Brown Design where he could be a real architect

again, not an architectural consultant. "I

got very tired of working with architects who didn't want to listen

to what their consultants were saying. I was trained as an architect

and what I really wanted was to get back into producing architecture."

Lucking talks proudly about Denver, which he now considers home, and of the city's fervent support of the arts. "People often underestimate us. It's not a cowboy town like most people think. And the weather is perfect!" Which caught us by surprise. He convinced us, as surely as he did his parents. "My parents are coming out for Carmen and my father phoned me. He said, 'OK, do I need to bring a big jacket?' I said, 'Dad, there is no snow.' It snowed three weeks ago and it went the next day. It's never that cold. Maybe a little bit at the end of January, February. No, our weather here is beautiful sunshine. And I think it reflects on the people here. We're always very happy."

Purely out of curiosity, we asked if he ever designed houses. "I

designed my own house in Mexico And I think it's wonderful. And if

you saw it

- the shape and the form of the house

- you would feel, you know, that I am a romantic."

|

|||||||

Design and Original Content: FanFaire LLC © 1997-2006. All rights reserved. |

|||||||

Meet

Peter Lucking, Meisterarchitekt, specialist in theater architecture.

Meet

Peter Lucking, Meisterarchitekt, specialist in theater architecture.

So,

what was basically left of the original structure?

So,

what was basically left of the original structure?  Lucking

never considered incorporating the neoclassical elements of the exterior

architecture into the design of the interior - which is totally modern,

Lucking

never considered incorporating the neoclassical elements of the exterior

architecture into the design of the interior - which is totally modern,

Like

most everything else, the stage is brand new.

Like

most everything else, the stage is brand new.  So

much for Peter Lucking, the architect. What about Peter Lucking,

the man? The tall, unassuming Denver transplant who wears a neat ponytail

is an Englishman raised in Cameroon, West Africa. He received his

architect's degree from Brookes University which split off from Oxford's

Magdalen College in the early 1970s. And believe it or not, he knew

even as a little boy that he was going to be an architect - which

is probably why he is a success at what he does.

So

much for Peter Lucking, the architect. What about Peter Lucking,

the man? The tall, unassuming Denver transplant who wears a neat ponytail

is an Englishman raised in Cameroon, West Africa. He received his

architect's degree from Brookes University which split off from Oxford's

Magdalen College in the early 1970s. And believe it or not, he knew

even as a little boy that he was going to be an architect - which

is probably why he is a success at what he does.

And

is Lucking, by any chance, an opera lover?

And

is Lucking, by any chance, an opera lover?