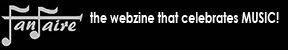

The critics loved to mock her – but in my eyes, Hildegard Behrens was no less than sublime

Hildegard Behrens is dead – only two years older than I am, and felled by an aneurysm in Japan, far from her Vienna woods. She is the reason I gave up going to performances of the Ring. I don’t want anyone else’s Brünnhilde to blur my memory of her doing it with the Vienna State Opera in April 1996. In her obituaries over the last fortnight, there has been a great deal said about her intelligence, her insight, her occasionally dodgy vocal quality – all of it true, but somehow missing the mark. She was sublime. What that means is that she was occasionally ridiculous. Her Tosca was ridiculous – on video, that is. You can’t – sorry, couldn’t – get what Behrens was doing if you weren’t seeing her live in an opera house, and sometimes not even then. It was partly a matter of the scale of her performance, which you’re not going to get if you’re poking a video camera down her throat. You’re not going to get it at the Met either, because the Met is just too vast. I don’t know what premonition sent me to Vienna that spring, but I am so glad I scraped together enough money for a good hotel and the occasional sachertorte mit schlag. Hildegard Behrens changed forever my understanding of the art of singing opera.

I had always been a stickler for perfect intonation, floating tone slicing its way through the orchestral texture by force of sheer purity, even in the most dramatic of operas. I thought Joan Sutherland had it pretty right, as she shaped ineffable ornaments like a craftsman cutting diamonds, each grace note perfectly in tune. You mightn’t have been able to distinguish Sutherland’s words in any language, but you never misunderstood the emotional colour of what she sang. She could add plangency that was heartbreaking, without straying from the middle of the note. Behrens was the opposite, a kamikaze pilot of a singer. Hers was an unadorned scream of a voice. As it rocketed through the winding and unwinding, leaping and bounding orchestral motifs, it was electrifying. Sometimes it burned up on re-entry; sometimes it crashed in a succession of hoarse gasps. At times like those, Behrens was ridiculed and even humiliated in the music press. By the time I went to see her perform in Vienna, she was losing her nerve. What was worse, because of the way she used her voice, it had begun to shred.

I found myself in the middle of the third row for all four operas. Donald Runnicles was conducting The Ring at the Vienna State Opera for the first time. When Behrens came on stage as Brünnhilde, I was momentarily aware that she was small and physically unimpressive, and rather too vain about the honey-blonde curls – her own – that bounced over her shoulders. What I wasn’t prepared for was the white-hot intensity of her concentration. She struck a pose at the beginning of each musical phrase, and then, keeping her body utterly motionless, launched her voice. There was no fiddling with her spear. No butch posturing. She was so far inside the music that if her costume had fallen off, she would not have reacted.

The opera house surrounded her singing as a frame surrounds a picture; as each motif was completed, it hung in the mind as if it had been drawn in light. Then she changed her position, and the process began again. As phrase built on phrase, I felt as if I had never heard that familiar music before. I learned then that pretty is enjoyable – but sublime exists on another level, beyond comfort, somewhere at the edge of the world.

Behrens had sung Brünnhilde to James Morris’s Wotan many times before, notably when she made her debut in the role at the Met in 1990. Runnicles’s unsentimental insistence on strict tempo suited her much better than had James Levine’s traditional schmalz and schwärmerei. On Runnicles’s firm orchestral armature, she erected a performance so shattering that, in act three of Die Walküre, even Morris was moved to a point where his voice turned gruff. From my seat in the third row, I could see him struggling with the lump in his throat.

After the performance, the word went out that Behrens was exhausted and terrified of singing in Götterdämmerung. The friends I was with went back to London, but I hung on, hoping against hope that she would put herself through it again. After a Siegfried in which Brünnhilde was sung by a soprano who is now singing all over the place, but whose fussy performance served to demonstrate how unutterably superior Behrens was, I ran up and down the opera house asking the attendants if they thought Behrens would sing in Götterdämmerung. They said: “This is her opera house. We will take care of her. She will sing.” And she did.

There is no chance that I will see a Brünnhilde so utterly destroyed, so uncompromisingly tragic ever again. I would have thought it impossible to show such a depth of devastation and helplessness in music, but Behrens did it. How she did it – whether by her utter absorption, her rapt earnestness or her lack of self-consciousness – I shall never know. Never to have seen her do it would be never to have understood how a preposterous musical drama, with absurdly affected DIY verse for a libretto, could be transmuted into the highest of high art.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/aug/30/germaine-greer-hildegard-behrens

![]()

Hildegard Behrens

As one of the great actor-singers of her generation, Hildegard Behrens seared herself onto the imagination as a Brünnhilde without equal, while claiming ownership of another Wagnerian heroine, Isolde, as well as Richard Strauss’ Salome and Elektra, Beethoven’s Leonore and Marie in Berg’s 20th century masterpiece Wozzeck.

Despite a late start - she was 26 and newly graduated as a barrister when she began singing lessons - Behrens was a natural theatre animal, full of dark, bristling energy and pent-up emotion that would explode on stage with overwhelming precision and power. Her commanding physical presence matched a dramatic soprano voice that, although prone to faltering, filled her characters with bursting believability.

Her professional debut in Freiburg in 1971 as the Countess in Le Nozze di Figaro prompted an invitation to join the Deutsche Oper. Herbert von Karajan’s championing of her as Salome in Salzburg in 1976 thrust her into the limelight. That same year, she made her debut at the Met - with whom she would sing 171 performances - and, as Leonore in Fidelio, at Covent Garden.

A Wagnerian without equal, she added a notable Isolde and Senta to a repertoire that also effortlessly embraced Mozart, Puccini and Janacek.

Though her voice proved erratic in later years, Behrens was still a box-office draw. Born on February 9, 2024 at Varel in northern Germany, she was in Japan preparing for a performance and masterclass at the time of her death from a ruptured aortic aneurysm on August 18.

She was married for a time to the German director Seth Schneidman, with whom she had two children.

http://www.thestage.co.uk/features/obituaries/feature.php/26018/obituary-hildegard-behrens

Hildegard Behrens: Operatic soprano acclaimed for her interpretations of Wagner and Strauss

The soprano Hildegard Behrens, who has died of a ruptured aortic aneurism aged 72, was an individual, unforgettable Wagner singer, a great actor and, for many, the definitive interpreter of Richard Strauss’ Salome and Elektra.

Born in Varel, not far from Hamburg in Germany, Behrens was the youngest child in a large family persuaded, like all her siblings, to take up an instrument by their music-loving doctor father (in her case the violin in addition to the piano). Graduating from her law studies at Freiburg University – a discipline which later came in useful when she negotiated her own contracts – Behrens took up singing there under Inés Leuwen. She started out belatedly in the lyric soprano repertoire, making her debut in 1971 as the Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and graduating via Fiordiligi and Weber’s Agathe to the lighter Wagnerian roles.

In 1977, alerted that there was a remarkable young singing actor who might meet his Straussian standards, Herbert von Karajan travelled to Dusseldorf to see Behrens in the lacerating role of Marie in Berg’s Wozzeck. He signed her up to sing Salome at the Salzburg festival, and the rest is history. From that, and the subsequent EMI recording, it was clear that from a tonal point of view, at last Strauss’s stipulation for the illusion of a “16-year-old princess with the voice of an Isolde” had been realised.

In 1978 Covent Garden audiences, who had already been able to witness the birth of a legend two years earlier, when Behrens sang Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio, saw that Salome for themselves – though this time there was no body double for the Dance of the Seven Veils, as Karajan had insisted on in Salzburg; Behrens performed the dance herself, as she was always subsequently to do.

Despite a vocal indisposition which Behrens was determined to ignore, her Royal Opera Salome was an electrifying interpretation. She started out with the silvery lightness of a gracious adolescent, developing with terrifying intensity into her crazed obsession for the head of John the Baptist. The great final scene married luminous fulfilment with disturbing mania. Never in recent memory has any soprano fulfilled so many of the role’s impossible demands so vividly.

Soon, Behrens progressed to the even more taxing demands of the revenge-crazed Elektra in Strauss’s violent next opera, a role she made her own in a blazing concert performance at the Royal Festival Hall and in a subsequent run at the Royal Opera. Leonard Bernstein chose her as his Isolde in a recording of Wagner’s great love story, which taxed her breath control to extremes with its slow tempi. She gave birth to a daughter during the run of performances.

She soon stepped into the heroic shoes of Kirsten Flagstad and Birgit Nilsson as Wagner’s Brünnhilde, very much on her own terms; with a lyric voice of dramatic potential rather than a true hochdramatisch capacity, the peculiar luminosity of Behrens’s instrument always carried to the back even of a vast theatre like New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Insistent use on a strong chest voice weakened the range and, in later years, the voice suffered from wear and tear, but her sheer commitment invariably carried all before it.

The traditional Met and under-energised Bayreuth productions of Wagner’s Ring demanded less of Behrens’s true dramatic potential than many would have liked to see, but she came into her own for Nikolaus Lehnhoff in Munich and in an unforgettable concert series conducted by Bernard Haitink at the Birmingham Symphony Hall and the Royal Albert Hall, London, as late as 1998. Brünnhilde nearly did for her, too, but not in the way it does for most sopranos: in 1990 the scenery fell on her during her immolation scene at the Met and, though she walked off stage, she was immediately hospitalised and subsequently took up a special vegetarian diet intended to help with the ensuing spinal problems.

In later years she progressed to roles which made demands of a different sort: the tormented Kundry in Wagner’s Parsifal, the Kostelnicka in Janác?ek’s Jenufa and Emilia Marty, the 337-year-old heroine of Janácek’s The Makropoulos Case. Her legacy in recordings follows her path from the sweet heroine of Weber’s Der Freischütz for Rafael Kubelik through to the unique Salome and the soldier’s mistress in Claudio Abbado’s sensuous interpretation of Wozzeck – a role also filmed – which gives a far stronger impression of her realistic acting than Brünnhilde in the conventional Otto Schenk Ring at the Met.

Behrens collapsed while giving master-classes and planning a recital at the Kusatsa summer music festival, to which she was a frequent visitor. She is survived by a son and a daughter.

• Hildegard Behrens, soprano, born 9 February 1937; died 18 August 2024

http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2009/aug/30/germaine-greer-hildegard-behrens

![]()

Hildegard Behrens

Hildegard Behrens, who died on Tuesday aged 72, was widely regarded as one of the greatest Wagnerians of her generation, a singing actress in the true Bayreuth tradition.

Her powerful portrayal of the composer’s Brünnhilde – a role she dominated throughout the 1980s and 1990s – led The New York Times to declare that “a new Wagnerian queen has emerged” when she captivated the Met in the new Otto Schenk production of 1983. Even in her sixties Hildegard Behrens’ voice could reach the back row of the largest opera house, notes finding their targets like well-aimed missiles, and emotion pouring forth with intensity.

While Brünnhilde was her calling card, Salome, Elektra, Emilia Marty (in Janacek’s Makropulos Case) and Tosca were among this formidable soprano’s repertoire. She enchanted audiences in the world’s leading opera houses, working under conductors including Leonard Bernstein, Georg Solti and Herbert von Karajan.

It was with Karajan – who had heard her rehearsing Wozzeck in Düsseldorf and signed her immediately – that she achieved international stardom as a mesmerising Salome at the Salzburg Festival in 1977, earning fame as one of the few singers to win an argument with the autocratic maestro. With Bernstein, she made an unforgettable recording of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in three sessions between 1980 and 1981, giving birth to her daughter just six weeks before the third act was committed to disc.

Although relatively late in developing an international career (she was nudging 40 before she was first heard in London), Hildegard Behrens’s voice, and the characters she chose to portray, were ideally suited to the older woman; and more than one critic noted that maturity brought fresh insights in her performance. In short, she was, as one judge observed, “reliable, but never merely predictable”.

In Bayreuth’s “British Ring” of 1983 (brought together by Solti, Peter Hall and William Dudley), Hildegard Behrens stole the show with a Brünnhilde in shiny black leather and sequinned studs. She looked, wrote John Higgins, “like a Saint Joan calling her amazon army to battle”.

Nevertheless, Hildegard Behrens was not without her detractors, who would unkindly compare her with Brünnhildes of old; indeed, she was destined to sing forever in the shadow of Birgit Nilsson, the Swedish Wagnerian who herself had suffered from not being Kirsten Flagstad. Meanwhile, Herbert Breslin, Pavarotti’s manager, referred to Hildegard Behrens in his notorious memoir as “the eccentric, gap-toothed German diva”.

Conductors and audiences, however, thought the world of her. The octogenarian Karl Böhm called her his “last great Fidelio”, while managers noticed that she was a box office draw on both sides of the Atlantic. Whether in opera or concert performance, she drew roars of approval and 15-minute standing ovations.

Hildegard Behrens was born on February 9 1937 at Varel, near Oldenburg, in northern Germany, the youngest of seven children of two doctors. Although she described her upbringing as a musical one, it was an elder brother who was marked out for greatness (he is a piano professor in Germany); the young Hildegard was dispatched to study Law at the University of Freiburg. She was 26 when she began to take singing seriously.

It was in Freiburg that she made her debut, as the Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro in 1971; five years later she was Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio at Covent Garden. When there was no understudy for her Salome in London in 1977, she went on stage with an indifferent voice – earning sympathy for her determination, rather than the condemnation she feared. From then on she rarely shrank away from the seemingly impossible, on one occasion singing Sieglinde in Die Walküre under Wolfgang Sawallisch having not touched the role for a year.

Although she lived latterly in the United States, Hildegard Behrens continued to maintain a formidable schedule, with regular appearances in Britain, including Bernard Haitinck’s magical concert performance of The Ring at Symphony Hall, Birmingham, and the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1998, when the aptly-named Siegfried Jerusalem was the ideal counterpoint to her darkly conspiratorial Brünnhilde.

A decade earlier her depiction of Strauss’ Elektra, with Christa Ludwig, under Seiji Ozawa at the Royal Festival Hall, was described by The Times as “nothing short of stupendous”.

On one occasion she was in Chicago to record Fidelio with Solti. While riding in a lift she began sweating, and Solti tried to comfort her: “Hildegard, don’t be afraid of me.” The singer retorted: “Maestro, I’m not afraid of you. I’m afraid of Beethoven.”

In 1990 she was injured during the final scene of Götterdämmerung at the Met when the great castle of Valhalla collapsed prematurely, burying her under an avalanche of foam rubber and leaving her with a bad back and black eyes. In the aftermath she became a vegetarian in order to lose weight and reduce pressure on her spine.

Hildegard Behrens, who won three Grammy awards between 1989 and 1992, died while at Kusatsu International Summer Music Festival, near Tokyo, in Japan, where she was a regular guest.

She is survived by a son and a daughter.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/culture-obituaries/music-obituaries/6056804/Hildegard-Behrens.html

![]()

Hildegard Behrens: Operatic soprano celebrated for her interpretations of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss

The German soprano Hildegard Behrens was a magnificent interpreter of the heroines of Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner. At the beginning of her career she sang several Mozart roles and such German classic staples as Agathe in Weber’s Der Freischütz, but as her voice grew stronger and her acting talents increased she seemed irresistibly drawn to characters such as Strauss’s Salome and Elektra, Wagner’s Isolde, Senta and Brünnhilde, all ladies who had very powerful feelings of one sort or another. Though she did not command the opulent tones of the usual Wagnerian soprano, she had such a keenly focussed voice that she could penetrate the loudest orchestral or choral passage, while the dramatic tension of her performances was almost tangible.

Hildegard Behrens was born in 1937 at Varel, near Oldenburg in North Germany, the youngest of six children. Her parents were both doctors, but everyone in the family played the piano and another instrument, in Hildegard’s case the violin. She studied law at Freiburg University, where she sang in student choirs, becoming a qualified lawyer before starting seriously to train her voice at Freiburg Music Academy. She made her debut in 1971 at Freiburg as Countess Almaviva in Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, then sang the same role in Osnabrück before moving to Düsseldorf, where she sang Agathe in 1973 and the following year, Marie in Berg’s Wozzeck. Marie was a dramatic role she continued to sing throughout her career, always with great success.

In 1974 Behrens also sang Fiordiligi in Mozart’s Così fan tutte and the title role of Janácek’s Katya Kabanova at Frankfurt. Her international career was about to begin, as she sang Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio at Zurich in 1975, and made her Covent Garden debut in 1976 in the same role. Leonora became one of her key roles, a dramatic tour de force that suited her vocal and histrionic gifts quite perfectly; she looked every inch the boy in her disguise as Fidelio, but her femininity was never in doubt, just below the surface.

Behrens returned to Covent Garden later that year as Salome, perhaps her most famous role of all. She could portray the amoral teenager with no difficulty, and 20 years later could still shed her clothes for the dance without embarrassment. Strauss might have written the vocal lines expressly for her, while in the final scene with the head of John the Baptist she exerted an horrific fascination.

Behrens also made her Metropolitan Opera debut in New York in 1976, singing Giorgetta in Puccini’s Il tabarro, one of her few Italian roles, returning two years later as Leonore in Fidelio. Meanwhile she scored a triumph at the 1977 Salzburg Festival as Salome in a production conducted and directed by Herbert von Karajan. The same year she gained another Strauss role at Düsseldorf, singing the Empress in Die Frau ohne Schatten. She repeated the Empress at the Paris Opéra in 1980. Meanwhile in 1977 she also sang her first Senta in Wagner’s Der fliegende Holländer at Zurich. Her performance was greatly admired, and she later sang Senta in Paris, Bonn and at the Metropolitan. In 1978 she sang Katya Kabanova with the Frankfurt Opera at the Edinburgh Festival.

Behrens returned to Zurich in 1980 for another new role, this as Isolde in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. Isolde became one of her finest interpetations: she repeated it in Munich that same year and at the Met in 1983. She returned to Munich in 1981 for the title role of Dvorák’s Rusalka, then sang Elettra in Mozart’s Idomeneo at the Met in 1982 before embarking on the enormous project of singing Brünnhilde in a complete cycle of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen at Bayreuth in 1983.

Behrens had sung Sieglinde in Die Walküre at Monte Carlo a few years earlier, but Brünnhilde was a different proposition, appearing in three out of the four Ring operas. The cycle was conducted by Georg Solti and directed by Peter Hall. In the event the production was not much liked – Bayreuth audiences are notoriously difficult to please – but Behrens was applauded by critics and public alike, for her magnificent performances.

Behrens sang Brünnhilde four years running at Bayreuth and inevitably her interpretation deepened with each repetition. The bright warrior maiden of Die Walküre became the lover in Siegfried and then the revengeful fury of Götterdämmerung before the resolution of the final scene when all was understood and forgiven. She sang complete Ring cycles at the Met, from 1986 to 1989, when at a performance of the final scene, the scenery collapsed before her exit and she was injured; in Munich in 1987; at the Vienna State Opera in 1992-93; and for the Royal Opera while Covent Garden was being reconstructed in 1998, semi-staged at the Royal Albert Hall and at the Symphony Hall, Birmingham.

Her next new role was Strauss’ Elektra, which she first sang at the Paris Opéra in 1987 and which immediately became one of her favouries. She sang the role in Munich, in London at the Royal Festival Hall, at the Met, in Athens, at Houston, in Buenos Aires, Montpellier and the 1996 Salzburg Festival. In the last three of thsse perfomances, the role of Klytemnestra was sung by Leonie Rysanek (once a radiant Chryso-themis, Elektra’s sister), and the scene between mother and daughter was particularly virulent. In 1997 she sang Elektra at Covent Garden and was still in magnificent form, always audible, never shouting, immensely poignant in the scene with her brother, Orestes.

Another new role, which she sang in Munich in 1980, was Emilia Marty in Janácek’s The Makropoulos Case in a production directed by her husband Seth Schneidmann. Marty was in every way suited to Behrens, but unfortunately she never had the chance to sing it again.

Another new and equally congenial role was Katerina in Schostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which she sang in Munich in 1993 and 1994. She sang “R”, a prostitute, in the world premiere of Berio’s Cronaca del luogo (“Chronicle of the Place”) at the 1999 Salzburg Festival, Marie in Wozzeck at San Francisco in 2000 and the Kostelnicka in Janácek’s Jenufa in the 2001 festival. Behrens taught and gave master classes after her retirement from the stage. In recent years she had attended the Kusatsu International Festival in Japan every August. This year she was taken ill on the way to Kusatsu, and died in hospital in Tokyo.

Hildegard Behrens, soprano; born Varel, Germany 9 February 1937; married Seth Schneidmann (one son, one daughter); died Tokyo 18 August 2009.

Hildegard Behrens

Soprano

Born: 9 February, 1937, in northern Germany.

Died: 18 August, 2009, in Tokyo, aged 72.

SHE was one of the most powerful Wagnerian sopranos of her day; indeed, many consider Hildegard Behrens ranked alongside Birgit Nilsson as an interpreter of the heavy German roles. Behrens principally made her career in New York and Germany and sang in the new production of The Ring Cycle – conducted by James Levine – at the Metropolitan Opera House to rapturous notices. The New York Times declared: “A new Wagnerian queen has emerged.” It was a remarkable achievement as Behrens made her debut on the opera stage aged 34 and her huge vocal range and her facility at the top of her voice allowed her to assume the most taxing roles. “I’m a long-distance singer. The longer, the better,” Behrens once said in an interview.

Because of her commitments in Bayreuth and Salzburg Behrens came to the Edinburgh Festival on just one occasion. In fact she sang only four roles at Covent Garden (Fidelio, Elektra, Tosca and Salome). The year 1978 was Peter Diamand’s last as artistic director of the Festival and he booked a particularly prestigious opera programme. Apart from a revival of Carmen (with Teresa Berganza) Diamand brought Frankfurt Opera to the King’s Theatre for just two performances of Janacek’s hugely demanding Katya Kabanova. Behrens sang the title role with a searing agility and won huge ovations at the end of her two performances. While the production was considered “unsympathetic”, the evening “was redeemed by the lustrous singing of Hildegard Behrens in the title role”.

Hildegard Behrens was the youngest of seven children, studied law at Freiburg University and started singing when she was 26, making her debut in Freiburg before guesting at other German houses. Her major break came in 1976, when Herbert von Karajan saw Behrens sing Berg’s Wozzeck in Dusseldorf. He booked her immediately for the following year’s Salzburg Festival in the title role of Salome. The production was a sensation and Behrens became an international star. She made her debut at Covent Garden in Fidelio, of which Opera Magazine wrote: “It is always exciting to be present when a new talent reveals itself for the first time.”

Her debut as Brunhilde was in the new production of Wagner’s Ring Cycle at Bayreuth in 1983. It was dubbed the English Ring as it was conducted by Georg Solti and directed by Peter Hall. It was not a total success – significantly, Solti cancelled conducting the following year – and Hall’s direction was not widely praised. But Behrens, dressed in shiny black leather and sequined studs, emerged with her reputation greatly enhanced. Her Brunhilde was always intense and feminine but blessed with great sympathy in her final scene with Wotan.

In fact Behrens and Hall worked well together but she found the mercurial Solti not so easy. Some years later she was recording Fidelio under Solti in Chicago. Going up in the lift to the studios the conductor saw his soprano was sweating badly. He reassured her by saying: “Hildegard, don’t be afraid of me.” “I am not afraid of you, Maestro” she retorted. “I am afraid of Beethoven.” In fact Behrens was never in awe of conductors such as von Karajan and Solti and, with her legal training, skilfully negotiated her own contracts.

Behrens recorded extensively and many of her performances are now classics. Apart from the von Karajan Salome, Behrens is heard on epic discs such as The Ring Cycle under Solti, Der Freischutz with Rafael Kubelik, Wozzeck under Claudio Abbado and Tristan und Isolde under Leonard Bernstein. The last was particularly exceptional as it was made in just three sessions in 1980, just six weeks before she gave birth to her daughter.

She did sing concerts in London and joined the Royal Opera for the company’s semi-staged production of The Ring Cycle at the Albert Hall under Bernard Haitink. In 1990 Behrens suffered from injuries sustained in New York when the scenery collapsed around her.

Behrens was a remarkable singing actress who had the rare ability to portray the thoughts and feelings of women pushed to the limits of endurance. Her preparation for every role was intense. “Taking one step onstage,” she said, “is almost impossible for me if I am not secure in knowing exactly what I want to do. It’s then you start to take risks – you go for what you have precisely in your mind. If you don’t risk much, you don’t gain much.”

Hildegard Behrens is survived by a son and a daughter.

http://news.scotsman.com/obituaries/Hildegard-Behrens.5583423.jp

![]()

Hildegard Behrens: operatic soprano

Hildegard Behrens was a German lyric-dramatic soprano in the classical tradition whose career spanned the last quarter of the 20th century. At her peak she was one of the leading exponents of the Wagner-Strauss repertoire and was particularly noted for her Senta, Brünnhilde, Isolde, Salome and Elektra, as well as Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio and Marie in Berg’s Wozzeck.

She was born at Varel, near Oldenburg, in Lower Saxony, the youngest of six children of medical practitioners. Their father, a talented amateur musician, required all of them to learn an instrument, and Behrens was set to learn the violin. In due course she went to Freiburg University to read law, and it was only after graduation that she began to pursue voice studies in earnest, at first in Freiburg with Inés Leuwen and then in Düsseldorf.

When her career blossomed, her legal training stood her in good stead, and she was wont to startle opera managers wishing to engage her by negotiating her own contracts.

Like one of her great predecessors, Kirsten Flagstad, Behrens was a late developer but, in compensation, was still able to sing heavy parts in leading theatres when well into her sixties. Behrens’s professional debut took place in 1971 as Countess Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro. She progressed steadily and successfully at German houses, including Düsseldorf and Frankfurt, in such roles as Fiordiligi in Così fan tutte, Giorgetta in Il tabarro, Agathe in Der Freischütz, Elsa in Lohengrin, Eva in Die Meistersinger and the title role in Janácek’s Kát’a Kabanova.

As Giorgetta she was coached by Oscar Fritz Schuh who spotted her at once as a natural, an instinctively theatrical animal who had no need to take any formal lessons in stagecraft, and, after Schuh’s advice, she never did.

A sort of turning point came when Herbert von Karajan, acting on hearsay, went to Düsseldorf to hear her sing Marie in Wozzeck, and at once asked her to be Salome in Strauss’s opera in a new production he was planning for Salzburg for 1977. When the Salzburg curtain fell the only criticisms to be heard were about the disruption of continuity caused by her being suddenly replaced for the Dance of the Seven Veils by a younger and more lissome creature, a professional dancer, but these complaints were targeted at the producer, von Karajan himself. Musically, the performances were a triumph, and were later preserved in an excellent commercial recording. Behrens, now much in demand for the part, took the complaints to heart and thereafter insisted always on doing her own dancing.

Meanwhile, the word having got around, she had been engaged by Covent Garden, where she sang Leonore in Fidelio in April 1976, a debut that caused the late Harold Rosenthal to write: “It is always exciting to be present when a great new talent reveals itself to an audience for the first time.” In the same year she arrived at the Metropolitan Opera, New York, as Giorgetta, and thereafter established herself on the global stage in such parts as Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, Tosca, Electra in Idomeneo, Senta in Der fliegende Holländer, Sieglinde in Die Walküre, Isolde, Brünnhilde in the Ring and Strauss’ Elektra.

Over the course of her career she sang in many of the great houses and festivals, including Paris, Munich, Vienna, and Dresden where, in 2000-01, she sang her first Kundry, having essayed the Parsifal character only in a concert performance in Cologne two years previously At Bayreuth she had the luck to make her first appearance as Brünnhilde in the ill-starred “English” Ring of 1983 conducted, at least to begin with, by Georg Solti whom she did not care for, and directed by Peter Hall whom she did esteem; and for the next ten years or so she was sought after everywhere as unequalled in the great hochdramatisch German soprano roles.

Her voice, in her heyday, was of captivating warmth and attractive timbre, though by no means of overwhelming size nor free of technical fallibility. She was, more importantly, a handsome woman and a singing actress in whom a masterly command of body-language and eloquent understanding of the text were combined with a stage persona of haunting vulnerability and femininity. It may be that this made her more compelling in moments of heartache or reflection than as the forthright warrior maiden, but those who heard her as Beethoven’s Leonore, as Strauss’ Elektra lamenting Orestes (“…und edler tausendmal, und tausendmal so wichtig…”) or as Brünnhilde making her peace with Wotan in Die Walküre (“War es so schmählich?”) will not soon forget it.

Her discography includes many of her most famous roles. As Agathe in Kubelik’s Freischütz the voice may be heard at its purest. At a similarly early stage in her career she was able to bring a comparable ingénue freshness to von Karajan’s Salome. But as the voice grew into its new hochdramatisch home, it inevitably lost some of that radiance. Yet for all her later vocal imperfections she rose magnificently to the challenges of the controversially slow tempos of Leonard Bernstein’s intense, proto-Mahlerian account of Tristan und Isolde.

Reminiscing about that Tristan recording she later recalled some charity performances she gave with Bernstein, which included Marlene Dietrich songs: “Lenny would be dressed in a sassy white tuxedo with glistening Lurex trousers and patent leather buckled shoes and I would be in Marlene-look with a midnight-blue evening dress, hat, cigarette holder and rhinestone-studded high heels.”

Under Claudio Abbado she reached the lyrical heart of the angular, expressionistic lines of Marie in Wozzeck in an account that was also filmed, as were her renditions of Brünnhilde in the traditional Otto Schenk staging of the Ring at the Metropolitan Opera under James Levine and in Nicholas Lehnhoff’s more searching, modernistic staging for the Bavarian State Opera under Wolfgang Sawallisch.

The latter account was issued on video and the short-lived laser-disc and although it has so far not been made available on DVD in Europe and North America, it was released in Japan, a country in which she enjoyed giving performances and masterclasses and where she suddenly died.

In 1995 Behrens was appointed Kammersängerin by the Vienna State Opera, an honour that gave her much pleasure.

Hildegard Behrens, operatic soprano, was born on February 9, 1937. She died of a ruptured aortic aneurysm on August 18, 2009, aged 72

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/obituaries/article6802369.ece

Obituary: Hildegard Behrens

The human voice takes on so many different characteristics that it’s improbable for any one singer to take on all the roles.

It’s just not possible, and sometimes a singer’s artistic inclinations can pull in opposite directions from their physical capabilities.

But every now and then a performer arrives of such versatility that they illuminate every role they take on.

Hildegard Behrens was probably the leading Wagnerian soprano of the 1980s and 90s, but she had a remarkably wide repertoire that could span anything from the delicacies of Mozart to the colossal challenges of Wagner and Richard Strauss.

She was blessed with a long career, too, performing at the highest level well into her 60s and still active right up to her sudden death in Japan on Tuesday.

Born in the small town of Varel, near the Danish border, she had studied first to become a lawyer at the ancient German university of Freiburg.

She went on to study music while at Freiburg, and it was there that she made her professional debut in 1971 at the relatively late age of 34, as the Countess in Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro.

Her career gathered pace rapidly, and she joined Deutsche Oper the following year and made her debut at the New York Met in 1976 in Puccini’s Il Tabarro.

At the same time, she was spotted by Herbert von Karajan and catapulted into the title role in Strauss’ Salome, at the Salzburg Festival, in 1977.

She was a regular at the Met right up to 1999, with her first leading part being Leonore, in Beethoven’s Fidelio, in 1980, under Karl Boehm.

But for all her versatility, she was best known for the big Wagner and Strauss parts, notably Brünnhilde, at Bayreuth, from 1983 onwards, and then at the Met from 1990.

It was at the Met that she earned her place in the story books after she was taken to hospital when the scenery fell on her during the final scenes of Götterdämmerung, although she was able to complete the performance.

Hildegard Behrens, singer; born, February 9, 1937, died, August 18, 2024

http://www.liverpooldailypost.co.uk/views/obituaries/2009/08/20/obituary-hildegard-behrens-92534-24486790/