![]()

Hildegard Behrens, Soprano Acclaimed for Wagner, Is Dead at 72

The German soprano Hildegard Behrens, a mesmerizing interpreter of touchstone dramatic soprano roles like Wagner’s Brünnhilde and Strauss’s Salome during the 1980s and early ’90s, died on Tuesday in Tokyo. She was 72 and lived in Vienna.

Her death was announced by Jonathan Friend, the artistic administrator of the Metropolitan Opera, in an e-mail message sent to associates and released to the media by Jack Mastroianni, director of the vocal division at IMG Artists and her former manager.

Ms. Behrens fell ill while traveling to a festival in Kusatsu, a Japanese resort town, to present master classes and a recital, and was taken to a hospital in Tokyo on Sunday night. She died there apparently of an aneurysm, Mr. Friend wrote.

Ms. Behrens’s ascent into the demanding Wagnerian soprano repertory was uncommonly fast after starting her career late. She did not begin vocal studies, at the Freiburg Academy of Music, until she was 26, the same year she graduated from the University of Freiburg in Germany as a junior barrister, having initially chosen law as a profession.

Her debut came in Freiburg in February 1971, the month she turned 34, in a lyric soprano role, the Countess in Mozart’s “Nozze di Figaro.” Her voice at the time was rich and flexible, and she might have continued on a lighter repertory path. But the shimmering allure and power of her sound and the intensity of her singing led her inexorably to Wagner.

In her prime she was a complete vocal artist, a singer whose warm, textured voice could send phrases soaring. Her top notes could slice through any Wagner orchestra.

Her technique made heavy use of chest voice, an approach that would eventually take a toll on her singing. Many purists argued that Ms. Behrens was no born Wagnerian. Her voice lacked the penetrating solidity of a Kirsten Flagstad or the clarion brilliance of a Birgit Nilsson.

Yet with her deep intelligence, dramatic fervor and acute emotional insights, she made her voice do what the music and the moment demanded. A beautiful woman with dark hair and a slender athletic frame, she was a poignant actress capable of fits and temperamental flashes onstage.

She was riveting as Wagner’s Isolde, a role she recorded with Leonard Bernstein conducting; Senta from “Der Fliegende Holländer”; and, especially, Brünnhilde.

She learned the three Brünnhilde roles of Wagner’s “Ring” cycle (in “Die Walküre,” “Siegfried” and “Götterdämmerung”) simultaneously, because she thought of the cycle’s four operas as an entity, an organic operatic drama. Her first Brünnhilde came with a complete “Ring” at the Bayreuth Festival in Germany in 1983, the production conducted by Georg Solti. It was a triumph for Ms. Behrens, which she repeated for the next three summer seasons there.

She sang the role when the Met opened its 1986-87 season with “Die Walküre,” the first installment of Otto Schenk’s production. In the spring of 1989 she sang in the Met’s first presentation of the complete Schenk “Ring,” which was designed with her in mind. The production was retired this May.

Between her Met debut as Giorgetta in Puccini’s “Tabarro” in 1976 and her appearances as Marie in Berg’s “Wozzeck” in 1999, she sang 171 performances with the company, including Leonore in Beethoven’s “Fidelio,” Elettra in Mozart’s “Idomeneo” and the title roles in Strauss’s “Salome” and “Elektra.” She sang the title role in Puccini’s “Tosca” opposite Plácido Domingo in the premiere of the popular Franco Zeffirelli staging introduced in 1985, a production later broadcast on public television.

Still, Brünnhilde became her Met calling card. She appears in the company’s DVDs of the Schenk “Ring” — recorded mostly in 1990, when she was at her dramatic and vocal peak — with James Levine conducting. The release affectingly captures her uncommonly feminine and thoughtful portrayal of this rambunctious character.

Yet Ms. Behrens’s move into Wagner was an act of will that took a vocal toll. By the mid-1990s, when she was approaching 60, her singing became ragged, with dicey pitch and strident top notes. Ms. Behrens drew criticism from many opera buffs and reviewers during this period. But she was determined to sing her chosen roles with uncompromising intensity, whatever the cost.

Hildegard Behrens was born on Feb. 9, 1937, in Varel, Germany, west of Hamburg, the youngest of six children. Both her parents were doctors, and her father was an avid amateur musician. As a child Ms. Behrens studied piano and violin and had a natural singing voice. Commenting on her musical upbringing in a 1983 interview with The New York Times, she said, “Nobody cared for me, and I had no expectations.” Hence her drift into law school.

Her true talent did not emerge until well into her vocal studies in Freiburg. In 1972 she joined the Deutsche Oper in Düsseldorf. She was discovered there by the powerful conductor Herbert von Karajan, who recruited her to sing Salome at the Salzburg Festival in Austria in 1977. The experience was exasperating for the determined Ms. Behrens: Karajan insisted that a nonsinger perform Salome’s Dance of the Seven Veils. Still, her performance was acclaimed

In the 1983 interview Ms. Behrens explained that she knew from the beginning that she would become a dramatic soprano, and that her slow start was an advantage.

“I consider my career to have had a fantastic logic,” she said, adding, “Now I realize that all that time I spent at the conservatory allowed me to evolve as a musician.”

“It was like playing a role out in my mind, before I actually did it. Even today I can think through a part, and my throat will subconsciously assume all the correct positions without my actually having to sing.”

By the early 1980s Ms. Behrens was such a major Met artist that she considered her loft in Chelsea home; she lived there at the time with her two children. Ms Behrens’s children, Philip Behrens of Munich and Sara Behrens Schneidman of Vienna, survive her, along with two grandchildren. She was married for a time to the German director Seth Schneidman, who directed her in several productions.

Ms. Behrens saw no divide between acting and singing. “Music for me comes out of the dramatic context,” she said in a 1997 interview with Opera News. “I have never had the temptation to view the voice as a fetish. For me it’s just a vehicle. I cannot consider it as some kind of golden calf.”

In 1990, while performing in the “Ring” at the Met, Ms. Behrens sustained a severe injury when a piece of scenery fell on her during the final scene of “Götterdämmerung,” the dramatic climax in which the Hall of the Gibichungs collapses. A beam of plastic foam and canvas stretched over wood fell prematurely and knocked Ms. Behrens to the floor, bruising her forehead and blackening her eyes. She had to miss subsequent performances. In a statement at the time, she said that if the beam had not struck her she might have taken a fatal fall into an open shaft created by a premature lowering of part of the stage floor.

Ms. Behrens was not an artist who looked back at decisions with regret, including her early choice of law school. She found helpful connections between law and opera.

“You go step by step in law,” she said in the Opera News interview, “and that’s what you do in opera too — finding motivations, reasons, cause and effect, emotions, guilt, responsibility. The intellectual training and discipline that it takes to solve a juridical case are very good for the approaches to a role.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/20/arts/music/20behrens.html

Singing the Praises of a Diva

IT’S strange to remember a diva best for a moment when she wasn’t singing, but Hildegard Behrens probably wouldn’t mind.

As Brunnhilde in the Metropolitan Opera’s 1988 production of Die Walkure, the great dramatic soprano listened to Wotan, king of the gods, relate his troubled history. For more than a quarter of an hour - motionless, silent - Behrens let the Wagner character’s wonderment and horror play across her face.

The emotions projected to the back of the auditorium. After the act, the woman in the next seat turned to me and marveled, “You don’t need to speak German to follow this story. She understands it all for you.”

Behrens was in Japan on Tuesday, preparing for a recital and master classes, when she died of an aortic aneurysm. She was 72.

Behrens was in Japan on Tuesday, preparing for a recital and master classes, when she died of an aortic aneurysm. She was 72.

Admired by her fans, she was esteemed by her colleagues as well. Soprano Deborah Voigt, who sang opposite her in Elektra, recalls a rehearsal when she reached out to comfort Behrens’ character.

“Don’t really touch me,” Behrens suggested. “It’s lonelier that way.”

Voigt reflects, “She knew so precisely what would provoke a response from the audience.”

Though her voice lacked the sumptuous warmth of Voigt’s or the sensual beauty of Rene Fleming’s, its silvery sheen and laser-like high notes won Behrens triumphs in such operas as Richard Strauss’ Salome.

When she sang the role of this teenage princess at the Met in 1990, she was 53 but sounded fresh and looked girlish in fluttering pink silk. In the long, exhausting final aria, her voice remained true and clear. That purity of tone was matched by onstage dignity. In an opera where most sopranos are content with shock value, she rose to tragic pathos.

Her gravitas was apparent also in her greatest role, Marie in Wozzeck. Playing a promiscuous woman murdered by her insane lover, Behrens never stooped to sensationalism or sentimentality.

She communicated the toughness necessary to exist in a brutal world while reminding us of the nobility inside even the most imperfect human being.

http://www.nypost.com/p/entertainment/theater/singing_the_praises_of_diva_XXs9XuSpwAIocwJ7Vi3nOO

![]()

Hildegard Behrens, 72, acclaimed opera singer

The Record

WASHINGTON POST NEWS SERVICE

Ms. Behrens performed in the best opera houses in the world alongside superstars such as Placido Domingo and under conductors including Leonard Bernstein, Herbert von Karajan and Georg Solti.

A latecomer to opera, Ms. Behrens was almost 40 when she first performed with the Metropolitan Opera. She spent more than three decades singing roles such as Wagner’s Brunnhilde and Strauss’s Salome, some of the most demanding in all of opera. Practically from her debut, she was known as an artist consumed by her characters, one who fully inhabited their lives.

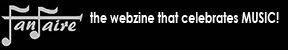

As Newsweek music critic Hubert Saal wrote in 1978, two years after Ms. Behrens’s first performance with the Met: “Many operatic sopranos, even some great ones, deliberately choose the roles that tax them least. Then there are likes of a Callas, a Sills, a Sutherland and a Nilsson — those superdivas who have sung to save their souls not their voices. A new sister has now joined their ranks — a young German soprano, Hildegard Behrens.”

Ms. Behrens lacked the hulking vocal power of traditional Wagnerian sopranos but compensated with the intensity of her acting. Some opera stars are content to stand onstage, barely acting, and let the audience bask in their voices; not Ms. Behrens.

“She was the consummate opera singer,” said Anthony DelDonna, who teaches musicology at Georgetown University. “She had a great stage presence — much truer to the ways her roles were envisioned” by their composers.

Ms. Behrens’s signature role was Brunnhilde in Wagner’s “Ring” cycle, which she sang most powerfully in the 1980s and ’90s, and which she performed in a well-received televised staging by the Metropolitan Opera.

Today simulcasts are commonplace, but at the time, Ms. Behrens was taking something of a risk.

Televised broadcasts had the potential to increase opera’s audience, DelDonna said, but a bad performance also posed the threat of increasing its pool of critics by turning a vast public audience off to opera. With her performance in the televised “Ring” cycle, Ms. Behrens helped put a face with her voice — and with Brunnhilde’s character — which many opera lovers had, until then, heard only on the radio.

Hildegard Behrens was born Feb. 9, 1937, in Varel, Germany, the youngest of six children. As a girl she took piano and violin lessons, then went to the University of Freiburg to study law. Yet she gravitated to the school of music and joined the school chorus.

At 26, Ms. Behrens decided to pursue music as a career. She began studying at the Freiburg Conservatory with Ines Leuwen, who reportedly said she had “a beautiful voice but no talent.” That judgment had the effect of liberating Ms. Behrens, giving her permission to sing her own way.

Her four years at the conservatory were the only formal training she received, a rarity in the opera world.

The untrained approach worked to Ms. Behrens’s favor, giving her voice a raw, visceral intensity. She made her debut with the Dusseldorf opera studio in 1971, when she almost 35, as the countess in Wolfgang Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro.”

Soon the powerful Austrian conductor von Karajan heard her in Alban Berg’s opera “Wozzeck” and quickly booked her for “Salome,” to be performed in 1977, in Salzburg. With von Karajan’s endorsement, Ms. Behrens launched her international career at London’s Covent Garden and at the Met, among other top opera stages.

What Ms. Behrens called the “most traumatic experience” in her career happened during a 1990 performance of Wagner’s “Gotterdammerung” at the Met, when a beam fell on her head. The accident caused serious damage, both physical and emotional, and Ms. Behrens told the magazine Opera News that it cost her three years of her life and career.

Survivors include two children, Philip Behrens and Sara Behrens Schneidman; and two grandchildren.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/08/19/AR2009081903913.html

![]()

Hildegard Behrens, Wagnerian soprano, 72

The singularity of opera star Hildegard Behrens’ life was summed up by the circumstances of her death.

At age 72, well past typical soprano retirement age, Ms. Behrens had been planning a recital and master class in Japan when, feeling unwell, she checked into a hospital Sunday, suffering from an aneurysm from which she died Tuesday.

No doubt she grieved over canceling. “I’m a long-distance singer,” she told The Inquirer six years ago. “The longer the better.”

Ms. Behrens was widely considered the most magnetic Wagnerian soprano of her time - not just for her singing, but for her acting as well - and enjoyed a stable family life in Washington, where she lived for many years with her husband and two children. Even during periods of ill health following a 1990 onstage accident, she insisted on continuing to sing. When she arrived for her 1982 Philadelphia Orchestra debut and discovered she was slated to sing an aria she had long since forgotten, Mozart’s “Come scoglio,” she relearned it and sang the program as advertised. When she was no longer hired to sing Wagner’s challenging “Immolation Scene” in the world’s opera houses, she sang it in recital halls, among them the Kimmel Center’s Perelman Theater in 2003, with success.

Ms. Behrens filled a considerable void in the late-1970s international opera scene as Birgit Nilsson was winding down her career with no clear-cut successor. Gwyneth Jones was having periods of uneven vocalism following a car accident; Roberta Knie was stymied by Metropolitan Opera politics.

Though Ms. Behrens earned a law degree at the University of Freiburg, in deference to her parents, she studied voice and theater all along. She was discovered at the mature age of 40 in her native Germany, during a run of Wozzeck in Dusseldorf, by the career-making conductor Herbert von Karajan. He immediately hired her to sing in his 1977 production of Salome in Salzburg for reasons that set the tone for her international career: She sang dramatic roles without a pile-driver voice, cut a handsome figure onstage, and knew how to project a characterization without even opening her mouth.

Customarily, Karajan recorded operas in Vienna prior to going into production in Salzburg, using the recordings during stage rehearsals to keep singers from wearing down their voices. But he was so intent on springing Ms. Behrens on the world that he made her lip-synch to an older Birgit Nilsson recording. Ms. Behrens was a sensation; her Salome recording is still considered the best of its kind.

She went on to become a conductor’s singer, perhaps because she wasn’t cowed by them. She argued bitterly with Karajan when he insisted that a dancer - not her - perform Salome’s dance of the seven veils. When recording Fidelio with Sir Georg Solti, the conductor told her not to be intimidated by him, to which she replied, “Maestro, I’m not afraid of you. I’m afraid of Beethoven.” Leonard Bernstein was so besotted with her talent after their Tristan und Isolde recording, he was seen in the audience at her Metropolitan Opera opening nights.

Ms. Behrens’ Met career began with ill-fitting Puccini roles, specifically Il Tabarro and Tosca. The Behrens voice never pretended to have the luster of more Italianate singers, though the theatricality she brought to Puccini was rarely equaled. What’s often a point of audience indulgence for chubby divas in Tosca was a Behrens high point: When her character jumps to her death from the fortress walls, Behrens appeared to literally embrace death with arms outstretched in a visual image that seemed both spontaneous and sculptural.

Not until the Met’s four-part, 16-hour Ring cycle, which was unrolled in the mid-1980s, was Ms. Behrens’ reputation consolidated with complete recordings of the saga and nationally televised videos. In that last medium, she became the human face of Wagner. The Otto Schenk production was a model of unfussy, pastoral realism, to which she brought an added humanity, often in camera close-ups in which she didn’t even sing. But in her periodic opera-in-concert performances with the Boston Symphony Orchestra - playing Elektra both in the Richard Strauss opera of the same name and in Mozart’s Idomeneo - she needed no scenery to create her character’s world.

During her 1980s vocal prime, however, Ms. Behrens sang performances that left listeners concluding her voice was shot; days later, she would emerge fresher and more brilliant than ever. Such vocal lapses became more than momentary, however, after 1990, when she was injured by moving scenery at the conclusion of a Met Gotterdammerung performance being taped for television.

At first, her injuries were said to be minor; the telecast was salvaged by video from rehearsals. In fact, Ms. Behrens had been knocked unconscious, leaving her with black eyes and back injuries. She became a vegetarian to lose weight and take pressure off her spine, but didn’t stop singing, even though she later admitted to giving performances she wasn’t proud of.

“I couldn’t stop,” she said. “Otherwise, I would never have been able to pick it up again. But it’s terrible when the [vocal] machine doesn’t work. Dreadful.” Later roles included Ortrud in Lohengrin, Kostelnicka in Jenufa.

Though the younger Ms. Behrens often seemed ill at ease offstage, she eventually responded to her star status with warm, attentive interactions with her admirers, even when strangers. A chance encounter with her on a Salzburg stairway could yield a detailed explication of the Luciano Berio opera she was premiering in the coming months.

News of her death prompted a degree of affection unusual even for opera fans. “I will never forget the way that she embraced Wotan during the final scene,” read one anonymous post on Operadepot.com. “It wasn’t as a valiant Valkyrie but as an awkward teenager daughter. . . . It was one of the most moving moments I have ever experienced in opera.”

http://www.philly.com/philly/news/breaking/20090819_Hildegard_Behrens__Wagnerian_soprano__71.html

![]()

Soprano Hildegard Behrens Dies At 72

One of opera’s finest voices fell silent yesterday.

German soprano Hildegard Behrens died unexpectedly of an apparent aortic aneurism while traveling in Japan. She was 72 years old.

For more than 30 years, Behrens sang many of opera’s most difficult, loud and lengthy roles, including Strauss’ Elektra and Salome and the lead in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde.

It was all the more amazing to hear such a huge voice emanate from the small-framed soprano. Behrens also portrayed more subtle characters: the countess in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, and Emilia Marty in Janacek’s The Makropulos Case.

But Behrens will probably be best remembered for her portrayal of the armor-clad Brunnhilde (all three roles) in Wagner’s Ring Cycle, when the 15-hour epic was first televised on PBS in 1990.

In her prime, in the 1980s and ’90s, Behrens was hailed as one of the greatest living Wagner singers, with the New York Times saying, “There does not seem to be another Brunnhilde to match her vocal authority, expressivity and dramatic perception.”

Behrens was on track to become a lawyer, earning a degree from the University of Freiburg. But she dropped the law books for music, singing small roles at the Deutsche Oper am Rhein, in Dusseldorf. That’s where conductor Herbert Von Karajan discovered her, in the mid-1970s, while rehearsing Alban Berg’s Wozzeck. The influential maestro asked her to audition for the demanding role of Salome, which she sang under his direction at the 1977 Salzburg Festival. She recorded the role with Karajan shortly afterward.

Behrens became a star Wagner singer at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where she sang until 1999, and at Germany’s Bayreuth Festival. Although her voice did not possess the laser-like power of the famed Birgit Nilsson, Behrens’ insightful dramatic skills helped make her one of the best loved Wagnerians of her generation.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=112029433

![]()

Soprano Hildegard Behrens dies at 72

Soprano Hildegard Behrens, whose fierce theatrical intelligence and vocal fearlessness made her a leading exponent of the dramatic roles of Wagner and Richard Strauss, died Tuesday in Tokyo at 72.

The cause of death was an apparent aneurysm, according to the Associated Press. She was in Japan for a series of performances and master classes.

Although her soprano did not naturally boast the heft required for the heaviest operatic roles, Miss Behrens made them her own through a blend of technical canniness and incisive dramatic intelligence. Even in her later performances, when her tone was often strained, there was no denying the potency she brought to such signature roles as Brünnhilde in Wagner’s “Ring” Cycle and the title role of Strauss’ “Salome,” both of which she recorded.

Miss Behrens was born Feb. 9, 1937, in Varel, Germany, a small town near Oldenburg, and grew up the youngest child of two physicians. She earned a law degree, but soon gave that up in favor of music, appearing in Düsseldorf and Frankfurt before making prominent debuts in London; Vienna and Salzburg, Austria; Bayreuth, Germany; and New York.

She made her San Francisco Opera debut in 1990 as Brünnhilde, just two months after being injured by a falling piece of scenery while playing the same role at the Metropolitan Opera. Chronicle music critic Robert Commanday extolled her San Francisco Brünnhilde for “the possessive radiance of her voice and singing, and the natural and persuasive nature of her characterization.”

She returned to the War Memorial Opera House two years later to sing Leonore in Beethoven’s “Fidelio,” and made her last appearance in 1999 as Marie in Berg’s “Wozzeck.” She also sang Leonore in a concert performance of “Fidelio” with the San Francisco Symphony in 1995.

Miss Behrens is survived by a son and daughter.

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2009/08/20/BARA19ATT8.DTL&feed=rss.classical

The syndicated reports (in English and other languages) by the following international news agencies were picked up by numerous media organizations throughout the world, a sampling of which is shown at the bottom of the page.

![]()

TOKYO -

Soprano Hildegard Behrens, one of the finest Wagnerian performers of her generation, has died while traveling in Japan. She was 72.

Jonathan Friend, artistic administrator of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, said Tuesday in an e-mail to opera officials that Miss Behrens felt unwell while traveling to a festival near Tokyo. She went to a Tokyo hospital, where she died Tuesday of an apparent aneurysm.

Mr. Friend’s e-mail was shared with the Associated Press by Jack Mastroianni, director of IMG Artists.

Her funeral was planned in Vienna.

Organizers of Miss Behrens’ visit said she was in Japan to perform at a music festival and then give lessons at a hot springs resort.

Miyuki Takebayashi, an official at the Kanshinetsu Music Association, said Miss Behrens was taken to a hospital Sunday night and died there Tuesday.

“Her son and daughter were at her bedside when she passed away,” she said.

Miss Behrens was among the finest actors on the opera stage during a professional career that spanned more than three decades. She made her professional stage debut in Freiburg, Germany, as the countess in Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro” in 1971 and made her Metropolitan Opera debut as Giorgetta in Puccini’s “Il Tabarro” in 1976.

One of her breakthrough roles came the following year, when she sang the title role in Richard Strauss’ “Salome” at the Salzburg Festival in Austria.

She sang 171 performances at the Met, where she appeared until 1999. She was most acclaimed in the late 1980s and early 1990s for her portrayal of Bruennhilde in the Otto Schenk production of the Ring Cycle, the Met’s first televised staging of Wagner’s tetralogy.

“She is the finest Bruennhilde of the post-Birgit Nilsson era,” Associated Press critic Mike Silverman wrote in 1989. “Though she lacks the overpowering vocal resources of a great Wagnerian soprano, she makes up for that with dramatic intensity as she changes before our eyes from a frisky young Valkyrie to a passionate and then betrayed lover, and finally to a compassionate woman whose sacrifice returns the ring to its rightful owners, the Rhinemaidens.”

A dramatic soprano, her Met career included Elettra in Mozart’s “Idomeneo,” Isolde in Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde,” Senta in “The Flying Dutchman,” Donna Anna in Mozart’s “Don Giovanni,” Santuzza in Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana,” the title roles in Strauss’ “Elektra” and “Salome” and Puccini’s “Tosca,” and Marie in Berg’s “Wozzeck.”

She was injured during the final scene of Wagner’s “Goetterdaemmerung” at the Met on April 28, 1990, when Valhalla collapsed prematurely and an overhead of foam rubber landed on her. Miss Behrens walked off the stage under her own power and was taken to Roosevelt Hospital.

She missed subsequent performances because of the injury and later sued the Met. Company spokesman Peter Clark said Wednesday the suit had been settled long ago.

According to Miss Behrens’ Web site, she was born in the north German town of Varel-Oldenburg. Her parents were both doctors, and she and her five siblings studied piano and violin as children. She earned a law degree at the University of Freiburg, where she was also a member of the student choir.

She received Germany’s Bundesverdienstkreuz (Order of the Merit Cross) and Bavaria’s Bayerischer Verdienstorden service medal and was honored by both the Bavarian State Opera in Munich and the Vienna State Opera.

![]()

German soprano Hildegard Behrens dies aged 72

TOKYO (Reuters) - German soprano Hildegard Behrens, best known for her roles in Wagner and Strauss operas, has died in a Tokyo hospital aged 72, an official at the Kanshinetsu Music Society Foundation in Japan said Wednesday.

Behrens, who was in Japan to participate in the Kusatsu International Summer Music Festival, near Tokyo, was hospitalized Sunday after arriving in Japan, said the official from the foundation, which hosts the music festival.

She died Tuesday of an aortic aneurysm, according to the foundation’s website.

Born in Varel, Germany, in 1937, Behrens started her musical training at a conservatory while she was a law student.

She made her professional opera debut in 1971 and went on to perform at the Salzburg Festival and leading opera houses around the world including the Metropolitan in New York and Covent Garden in London.

Among her accolades were three Grammy awards for best opera recording between 1989 and 1992.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/08/19/us-behrens-death-idUSTRE57I39220090819

![]()

Opera singer Hildegard Behrens dead at 72

TOKYO, Aug. 19 (UPI) — German opera singer Hildegard Behrens has died in a Tokyo hospital after falling ill last weekend. She was 72.

The BBC reported the celebrated soprano had been in Japan to perform and teach workshops at a music festival.

A spokesman for Kusatsu International Summer Music Academy and Festival told the British broadcaster Behrens died Tuesday afternoon after suffering an aortic aneurysm.

During a career that spanned more than three decades, Behrens earned accolades for her memorable portrayals of composer Richard Wagner’s heroines.

She performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House 171 times between 1976 and 1999, and was presented with Germany’s Order of the Merit Cross and Bavaria’s Bayerischer Verdienstorden honor, the BBC said.

A SMALL SAMPLING OF THE MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS THAT USED THE ABOVE SYNDICATED NEWS REPORTS: